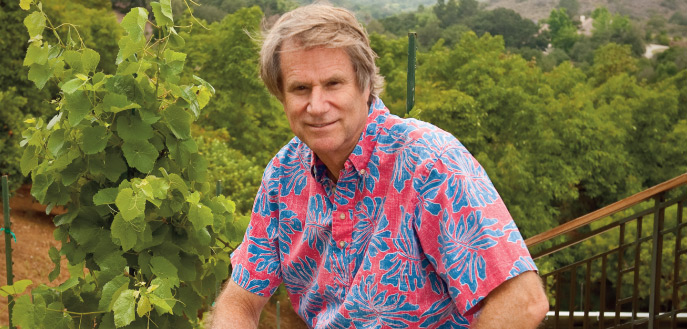

Professor Don Deardorff has studied with a Nobel laureate, mentored a Rhodes Scholar, and had chickens running around his Norris Hall office. Is it any wonder he'll be missed?

By Peter Gilstrap | Photo by Kevin Burke

Over the last three decades, hundreds of Professor Don Deardorff's students have gone on to impressive careers in chemistry, medicine, law, and business. Countless numbers of his avocados, meanwhile, have gone into some of the finest guacamole imaginable.

Teaching organic chemistry and farming avocados are the two major passions of the beloved Dr. Deardorff, who is retiring this summer after 34 years at Occidental. His understated charm, enthusiasm for learning, and infectious sense of humor have made an indelible mark on the College. He has mentored a record seven Goldwater Scholarship winners and five National Science Foundation Graduate Fellowship recipients, as well as Oxy's most recent Rhodes Scholar. He has been awarded numerous distinguished grants, published landmark papers on organic synthesis, and been a tireless champion of undergraduate research—a hallmark of the Oxy academic experience.

As if that weren't enough, the professor has also received the Beat a Dead Horse Award, the coveted Jerk of the Century trophy, and his treasured World's Biggest A**hole mug, all bestowed upon Deardorff with great love and irony by some of Oxy's brightest student scientists, many of whom credit him with changing their lives.

"My students are always decorating the office," Deardorff chuckles, gesturing around the happily cluttered room he's occupied for three decades. "I came in last August, and they had put the head of a warthog on the wall and fish and animal skins everyplace. When I got promoted to full professor, I came in and they'd put in two bales of hay and two chickens, and the chickens were wandering around and had crapped all over the place."

But when they're not in his office for prank-based concerns, Deardorff's students are often there seeking advice on matters academic and personal. "He's made the most impact on my life of anyone that I've ever met," says Anasheh Sookezian '14, now a Ph.D. student in organic chemistry at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. "The way he ran his lab, it really made me realize that that's what I wanted to do. I wanted to be like him—I wanted to be a professor at a small liberal arts college and have a lab like he does to be able to inspire students like myself in the future."

Growing up in San Francisco, Deardorff's interest in chemistry was sparked as a child. "I started out the way a lot of kids did," he deadpans. "I made things that blew up." He studied electrical engineering at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo, "which was a lot of work. Finally I just said, 'I don't have to work very hard at chemistry,' so that's why I switched over to chemistry." (He graduated with degrees in both chemistry and biochemistry in 1972.) Deardorff earned his Ph.D. from the University of Arizona in 1979, followed by work as a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard University under E.J. Corey, who would win the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1990.

This is kind of a big deal, though Deardorff is not one to brag—"I don't like to talk about myself," he gripes. "It's hard to do!"

Cullen Taniguchi '98 offers some perspective. "He was part of [Corey's] team that completed a complex synthesis of a beautiful molecule called aplasmomycin, which is still considered one of the greatest synthetic accomplishments made by the Nobel laureate's lab."

It was something that swayed Taniguchi to enroll at Oxy from Mililani High School in Hawaii. "A guy with that kind of resume could have gone anywhere, and I was very impressed that he came to Oxy," says Taniguchi, now an assistant professor at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

"He was kind of a rock star professor. Students flocked to him, and he was always a center of activity. He had a great research group, and I stayed with him from when I was a freshman until the summer after I graduated. We published three or four papers together, and my work with him earned me a Rhodes Scholarship and a full scholarship to Harvard Medical School," Taniguchi says. "I owe a lot to his mentorship."

What, exactly, is the Deardorff magic?

"One thing I've learned is that there are numerous approaches to teaching, and most of them are equally good," Deardorff says. "You can be a solid teacher and get a lot out of your students without having to beat 'em up. If you make it fun, they'll love it."

Among his many skills, "making it fun" ranks high. "I would characterize him as being the heart and soul of the department for the last three decades," says chemistry professor Michael Hill, a Deardorff friend and colleague for 21 years. "You walk in the [Norris Hall of Chemistry] building and you hear the pipes banging, and you're cold because it's not heated and you see the paint peeling, but what you also hear are people laughing and engaged in their work. He has really made this department like a family, and that sense of community is what drives our success."

Jeffrey Cannon '07 bolsters the family analogy: He joined Deardorff's research group as a freshman, and returned to the College last fall as an assistant professor of chemistry—a tenure-track position—just as his former mentor departs.

"When you're a student it seems like he's just kind of there to make sure you're not hurting yourself," Cannon says, "but the reality is that it gives the students a feeling of power and accomplishment and independence, and he's actually very involved. That's something that I didn't realize until now, now that I'm kind of in the same position."

That's not the only lesson handed down. "He taught me how to write," Cannon adds. "He writes the most incredible letters of recommendation. They're works of art, every single one of them."

Now Deardorff's works of art will be the avocados he lovingly tends—"Farming is 90 percent chemistry"—on his 27 acres near Temecula, land he began buying in 1988. "I went down there and looked around, and I bought a five-acre grove," he says. That land has seen annual Oxy research group parties, which will no doubt be missed. "You walk out in the grove, and all the stress leaves you. It's just shady and gorgeous underneath them. I've always loved avocados. I'm usually very deliberate before I make any decisions, but anything having to do with barbecues or avocados I jump."

Reflecting on his years at Occidental, "the school's been great," Deardorff says. "Been a lot better than I deserve, and I have no complaints. I just want to get out while I can still enjoy doing something else."

Peter Gilstrap wrote "Phoebe Dearest" in the Spring issue.