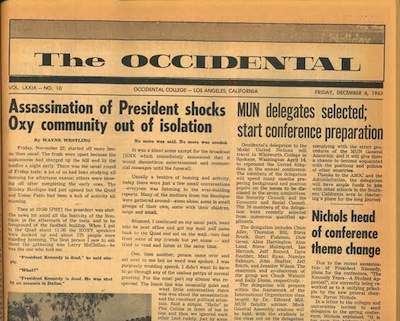

In Los Angeles, JFK’s assassination was a mid-morning event. I was a senior at Occidental, having morning coffee when a friend barged into the Student Union, yelling that the president had been shot.

We rushed to the Quad. The college radio station began to broadcast a network news feed through outdoor speakers, and the crowd grew quickly as the next set of classes let out and heard. JKF shot? Badly? Now what?

For many of us, JFK wasn’t just the president. He was the president who carried the torch to a new generation –- to us! The televised debates with Richard Nixon in the fall of 1960 were formative, collective moments as our freshman year began. The Cuban Missile crisis in 1962 had brought us to the same Quad just one year earlier, when we stopped going to classes to await together our nuclear devastation that we realized could happen at any moment if the USSR attacked the extensive aerospace industry in the L.A. basin.

Months later, as graduation grew closer, classmates were debating whether to join JFK’s newly minted Peace Corps. Kennedy’s phrase about "making the world safe for diversity" appealed to our geo-political idealism, although we were too naïve to see any connection to a civil war in Vietnam.

But there had also been JFK’s Bay of Pigs fiasco, his inability to push his legislative agenda forward and doubts about his response to the civil rights movement. By the fall of 1963, JFK and the "Kennedy years" seemed so momentous that a small group of us seniors were organizing a national student conference for the spring of 1964 to evaluate Kennedy’s presidency prior to the 1964 election. We had just held a planning meeting the day before. Now what?

The crowd in the Quad numbered several hundred by the time the radio feed announced that JFK had died. It was just after 11 a.m. in L.A. We heard the news together, faculty and students, alone in our thoughts but connected closely by a sense of community. We milled about aimlessly as the broadcast continued, several people crying, some caught up in fear and all stunned into silence as we touched hands or put our arms around shoulders. A revered senior history professor, a WWII refugee from Germany, stood alone with an unlit cigar in his mouth and tears on his cheeks. The College president came to the Quad to announce in person that classes for the rest of the day were cancelled and that an impromptu memorial service would be held that afternoon.

Almost nobody went to lunch as noontime arrived. We just stood in Quad, listening to the radio feed, waiting for someone to tell us the meaning of that morning.

--Byron Nichols ’64