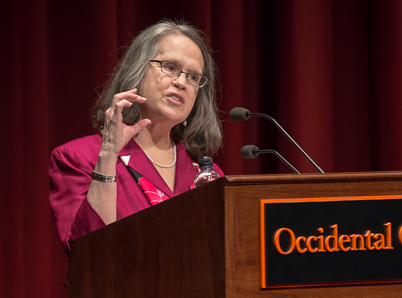

Harvard's Karen L. King returned to Occidental, where she began her academic career, to give a February 7 talk about her recent discovery of a fragment of Egyptian papyrus in which Jesus refers to "my wife."

In her lecture in Keck Theater, King -- the Hollis Professor of Divinity at Harvard -- discussed her discovery and what is at stake in these debates for Christian teaching about sexuality and desire.

King cautioned that the small papyrus fragment she unveiled in Rome in September is not proof that Jesus was married. The Coptic text was likely written long after Jesus’ death, and all other early, historically reliable Christian literature is silent on the issue.

But her discovery is the first known text from antiquity that refers to Jesus speaking of a wife. It provides additional evidence that there was an active debate among early Christians about whether Jesus was celibate or married, and what that meant for his followers.

Despite these careful qualifications, the response to King’s research was swift and in some cases so vicious –- and global -- that Harvard installed a panic button in her office, she revealed in her talk.

"I was pretty surprised by the furor," she said. "I’ve learned how important these issues are to people. Clearly these are not ‘antiquarian’ issues. I also learned how nasty people can be." She said she created one file for emails she labeled "Poison."

"The claim is really quite modest," she said. The papyrus "is not evidence that Jesus was married. But it is evidence that it is what early Christians wrote."

Describing how she was first approached by the private owner of the papyrus in July 2010, King said at first she assumed the piece was a forgery. But when she began comparing the wording to early Christian texts, she found similar phrasing. It was enough for her to take the sample to one of the premier papyrologists in the country for analysis. It took two years to change her opinion, she said, but in the end she became convinced the scrap dated to the 2nd century AD. (Tests on the papyrus and ink are ongoing to verify its authenticity.)

A "much more interesting question" than the issue of whether or not Jesus was married –- which will never be proven or disproven, King said -– is "why did the topic of whether or not Jesus was married come up at all?" among the early Christians. "What was at stake in Jesus’ marital status? What was at stake then, and what is at stake now?"

"The topic of whether to marry or not was a subject of lively debate from the earliest years of Christianity," she said. The notion of Jesus’ celibacy, King said, became a model for the structure of both the Christian church and the Christian community that extends to this day. An unmarried Jesus, whose "bride" was the church, established the gender and sexual structures of families, society and monastic life, including the development of a celibate male leadership, she said.

Thus, a challenge to the idea that Jesus was unmarried is a threat to the very foundations of the Christian church, and that is why the little slip of papyrus has engendered such an "intense" and "passionate" response, she said.

King concluded by saying that she hopes the media focus on the significance of the papyrus will shift from its authenticity to the issue of the Christian church’s attitude toward sexuality in general, which has long been deemed "dirty" and associated with "Eve’s sin," with serious negative consequences for women through the centuries.

King, who was profiled in the New York Times in September, is well known for her contributions to the scholarship of early Christian history and literature. Her books include The Secret Revelation of John, The Gospel of Mary of Magdala: Jesus and the First Woman Apostle, What Is Gnosticism, and Revelation of the Unknowable God. Other publications include Images of the Feminine in Gnosticism (ed.) and Women and Goddess Traditions in Antiquity and Today (ed.)

King was a popular professor in the religious studies department at Occidental from 1984 to 1997 and also helped found the women’s studies department, which she chaired for many years.