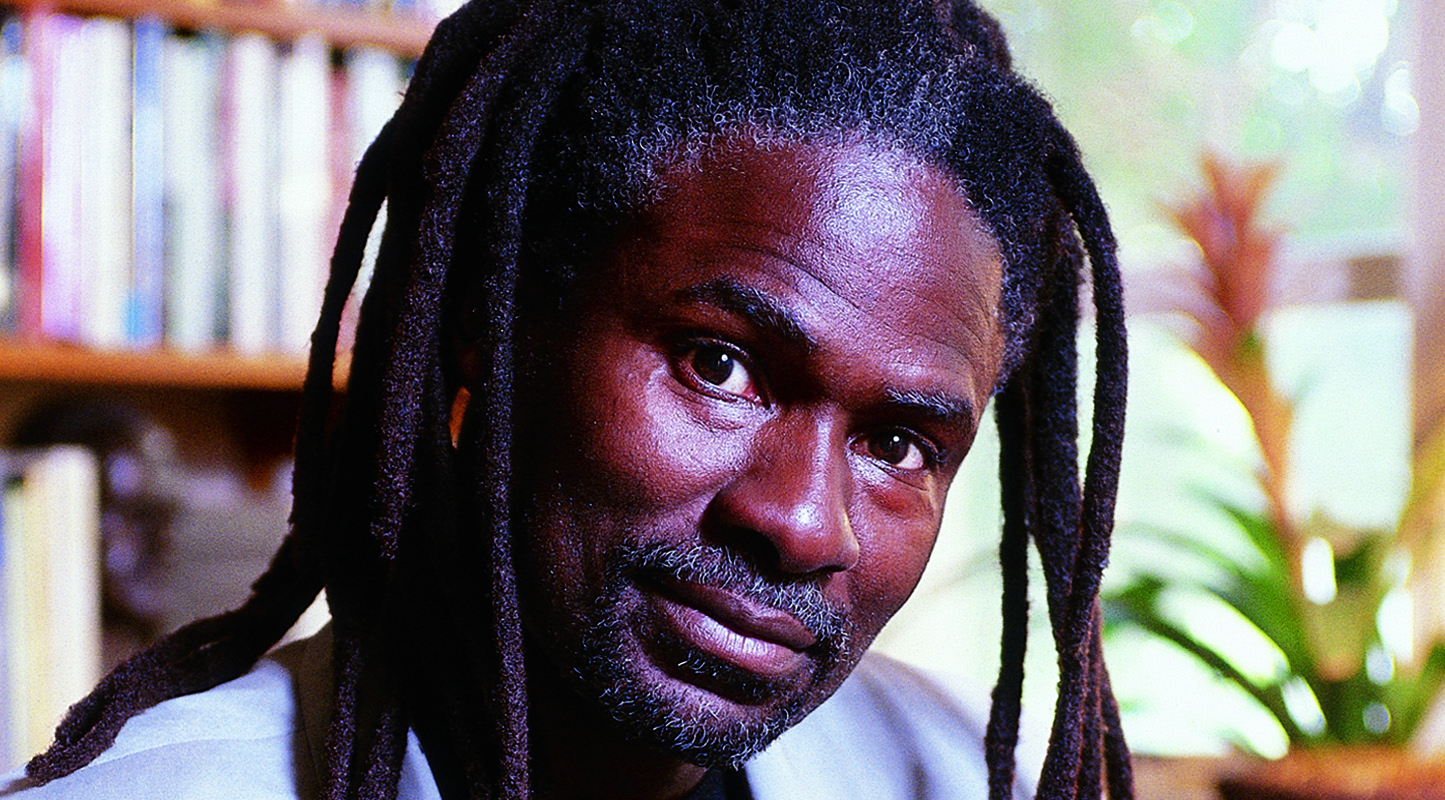

From Fall 2001: With a curriculum that incorporates psychology, religion, Rastafari, and racism, Associate Professor Elmer Griffin challenges his students to reimagine the world

(Editor's note: After 35 years, Glenn A. Elmer Griffin retired from Occidental last December as professor emeritus in the Department of Critical Theory and Social Justice. A three-time recipient of the Donald R. Loftgordon Award for Distinguished Teaching, he was profiled in Occidental magazine in Fall 2001. A tribute by Jill Normington ’94 follows the article.)

Elmer Griffin’s query sounds simple enough. “How many of you are white?” he asks. Most of the 30 newly enrolled students in his Religious Studies 390 course—provocatively titled “Whiteness”—raise their hands. The four Latino and African American students aren’t sure what to make of the query. “They know that this is a tricky question or there’s a problem somewhere,” says Griffin, associate professor of psychology and religious studies at Occidental. “It’s a really interesting pedagogical moment.”

Several such moments unfold during the months that follow, many of them revealing explorations into the dynamics of racism. “Students appear to be seeing themselves for the first time,” Griffin says. “By the end of the class, it will be impossible for them to be white. It will be like trying to write a bad check at the grocery store.”

Griffin sets out to deconstruct whiteness as a choice rather than a biological fact—more about mindset than the color of one’s skin. Whiteness, he asserts, is reflected in many lights, from those who argue that multiculturalism has gone “too far,” to his fellow West Indians who spurn Griffin’s trademark dreadlocks as a reminder of the poor, uneducated, and drug-dependent element of Caribbean culture. “They insist adamantly that their rejection of Rastafari is not a product of their colonization of mental slavery,” Griffin says.

While his message rankles some and evokes the occasional second-hand charge of reverse racism, he says no one has ever levied the accusation to his face. “I am not concerned about that,” says Griffin, a two-time recipient of the Donald R. Loftsgordon Award for Distinguished Teaching, as voted by the senior class (in 1992 and again this year). “Critical white studies is an intellectual task in which reactionary gestures and simplistic reversals such as ‘reverse discrimination’ cannot play much of a role. Whiteness is nothing but an ideology of supremacy. It’s not race, it’s not genetic or biological.” Says Loren Alhadeff ’01, a religious studies major from Seattle: “He’s always up for new ideas. He always says to me, ‘Don’t tell me anything I’ve already heard or already know.’ His classes are brilliant and insightful, to say the least.”

Griffin is first to admit that he preaches to a choir already versed in the precepts of racial unity. “I’m trying to make the choir sing a new song,” he says. “This is not a course designed for students who are dealing with racism for the first time.” If there’s anything discouraging about his role, it’s the indifference or even hostility his students are met with when they try to discuss critical white studies in the world at large. “They’re seen as race traitors,” Griffin says. “Family and friends won’t indulge them and they’ll stubbornly resist the idea. What I hear most is they’re sealed off, impenetrable, and refuse to get it.”

Griffin’s courses tackle “provocative subjects, but they absolutely belong in our curriculum,” says David Axeen, vice president of academic affairs and college dean. “Elmer and I have had many arguments, but I have always enjoyed those encounters. He is a great debater, in part because he is willing to concede a point every now and then. We used to play tennis together, and it would not surprise you to know that he had a powerful serve.”

Landing a seat in one of Griffin’s courses isn’t easy. His classes generate long waiting lists, with Clinical Psychology and Rastafari, Reggae, and the African Diaspora both student favorites. In the latter, Griffin plays music by rappers to demonstrate the influence of West Indian musical and political sensibilities on the American identity, including the continuation of civil-rights era radicalism (Tupac Shakur) and gender politics (Lil’ Kim). “All the great West Indian intellectuals have something to say about Rastafari,” says Griffin, who requires students to read the work of political theorist C.L.R. James, psychologist and revolutionary writer Frantz Fanon, and Caribbean poets Derek Walcott and Kamau Brathwaite. “If you graduate from a college that describes itself in the way Occidental does, and you don’t recognize the work of West Indian intellectuals,” he says, “there’s something crucial missing in your education.”

Griffin, 40, arrived at Oxy in 1989, lured in large part by the College’s commitment to diversity. The second-oldest of six children, he was born on the tiny West Indian island of Nevis, a former British colony famous for being birthplace of Alexander Hamilton and known for having one of the highest literacy rates in the world. After attending Caribbean Union College in Trinidad, Griffin immigrated to the United States because he perceived it as “the center of the world.” (“Most West Indians of my generation no longer believe this and value the Caribbean more than they used to,” he notes.) He completed his bachelor’s degree at Pacific Union College in Napa Valley and enrolled at Fuller Theological Seminary in Pasadena, where he simultaneously worked toward a master’s in theology and a doctorate in psychology. “Although I wanted to be a clinical psychologist, I was aware that psychology was philosophically, politically and ethically limited as an enterprise,” Griffin explains. “‘Should I leave my husband?’ is a moral question. Psychology doesn’t easily recognize itself as a political and moral enterprise; theology does.”

He divides his time between the Psychology Department and the Religious Studies Department, where he has spent the last two years as chairman. He has published papers on topics including the politics of golf in the Eastern Caribbean and “purchaser bias” in independent psychological assessments of depression. In addition to his work as an expert witness in Los Angeles, Griffin will soon return to the Caribbean to offer testimony in an upcoming case in which a Jamaican murder defendant is accused of killing in the name of “Obeah,” an Afro-Caribbean shamanism associated with evil spirits and ritualism.

Back at Oxy, Griffin’s coursework is infused with warnings to students about what he sees as the dangers of liberalism. As this year’s Loftsgordon winner, Griffin spoke to the graduating class with typical candor. “Liberals are genuinely well-meaning people with good hearts who earnestly talk the talk of inclusion and diversity—people who generally feel it when they say, ‘I see the injustice and I want to help.’” But, Griffin adds, empathy can result in overconfidence that causes well-meaning people to substitute their own goals for what is best for the beneficiary.

If Griffin creates restlessness among his students, that’s his intent. His courses are difficult (requiring seven papers), and class discussions can be enervating. “It does take a toll on you,” Alhadeff says. Griffin draws on existing whiteness theory and assigns seminal writings on the subject that include Race Traitor, by Noel Ignatiev and John Garvey; Critical White Studies, by Richard Delgado and Jean Stefancic; and Even the Rat Was White, by Robert V. Guthrie. Much the way Black, Chicano, and women’s studies were fledgling academic areas in the 1960s and 1970s, whiteness is a new, and sometimes misunderstood, pursuit. “This is a legitimate academic subdiscipline,” Griffin says. “This is an academic endeavor that promises new ways of thinking about a stubborn problem.”

Griffin got his idea for the class in 1998 when he spoke at a high school race forum in Hollywood. His talk centered on how children become racists, beginning with what he calls “an apprenticeship in whiteness.” “I didn’t want to give another talk about how people of color have suffered and been victimized,” Griffin says. “I think people have gotten acclimated to the stories of anguish and have numbed themselves to stories of victimage. Psychobabble has taken over discussions about race. People have inoculated themselves against the strategies that have worked in the past, and it’s urgent we find new ways to deal with race.”

Though recent news accounts might suggest otherwise, Griffin is optimistic about the future of race relations in America. “To me, the increasingly gross, crude, boorish manifestations are death throes,” he says. “I have the comfort of an assured victory. If the battle is won in principle, then the ongoing bloody skirmishes are just a matter of time.”

Griffin is passionate in the classroom, an intensity he traces back to his own undergraduate experience. “I had professors who made me feel that ideas really mattered more than anything,” he says, and those impressions heavily influence his own academic agenda. “I want students to realize the world around them can be unmade and remade. Things are not the way they are because they have to be. For me, examining and detailing the forces of processes that give us the world we have now is a central academic task.”

Jill Normington ’94: If you’re looking for an example of what a small college experience is supposed to provide, you will find Elmer Griffin at the heart of it. Thoughtful lectures filled with interesting professional endeavors, engaging class discussions that included even the soft talkers, tough reading assignments from Foucault and Freud forcing you to reexamine the way you look at the world and yourself—he gave all of that to the students who took his classes.

Dr. Griffin was more than the professor who taught my most fascinating courses; he was a mentor and a friend. He invited me into his research, encouraged me to present that work at conferences, and gave me co-authorship credit on papers. He helped me get summer jobs in the field and introduced me to colleagues who could expand my knowledge. And Dr. Griffin demonstrated work ethic and generosity. He bought me dinner at Señor Fish more times than I can count and helped me with my short game. He shared his love of dub poetry and reggae.

I live far away now and have only made it back to one reunion, my 25th. I sat outside Dr. Griffin’s office and listened to him counsel a current student, and when he popped his head out to see me sitting there, his wide, welcoming grin was confirmation that our genuine connection remained. Thank you, Dr. Griffin, “Mi Revalueshanary Fren,” for helping to give me confidence in myself.

Jill Normington ’94 is the owner of Normington Petts, a Democratic polling firm in Washington, D.C.