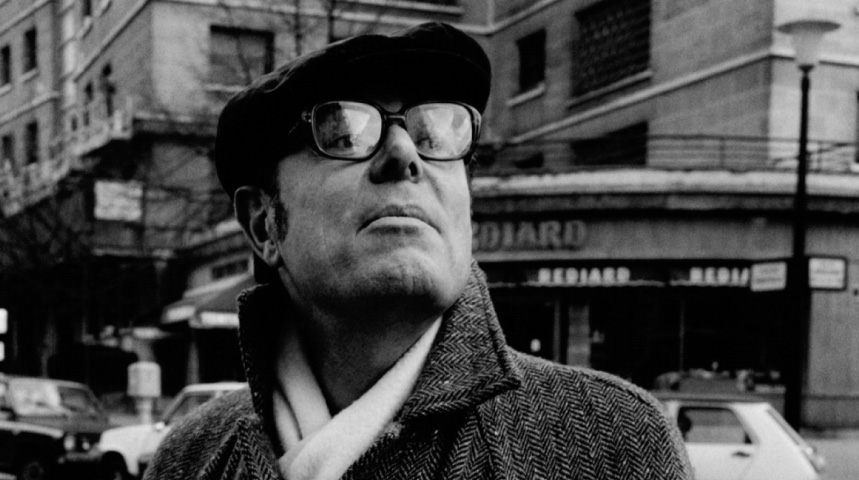

Academy Award-winning documentary filmmaker Marcel Ophuls ’50, who attended Occidental for three years before dropping out to finish his studies at the Sorbonne, died May 24 at the age of 97. Ophuls reflected on his time at Oxy—and his reasons for leaving—in a 2005 profile in Occidental magazine.

It might come as something of a bombshell that Oscar-winning documentary filmmaker Marcel Ophuls ’50 is no great tan of the genre. “Put that in there,” he says by phone from his home in Lucq-de-Bearn, France. “I always like to surprise people. It’s such a puritanical business. Most documentary filmmakers are anti-Hollywood and anti-show business, and I happen to be the son of a great director and my mother was an actress.”

Ophuls’ oeuvre, however, is marked by a pair of documentary classics: The Sorrow and the Pity (1970), the epic story of Nazi-occupied France; and The Memory of Justice (1976), which examines guilt, responsibility, and the horrors of war from the Nuremberg trials through Vietnam. In 1988, Ophuls won for Hotel Terminus: The Life and Times of Klaus Barbie, about the Nazi war criminal known as “the butcher of Lyon.”

Occidental played a major role in shaping Ophuls’ work. After moving to the United States from France in July 1941, the German-born Ophuls graduated from Hollywood High School, enlisted in the Army, and enrolled at Oxy on the G.I. Bill. During the years following World War Il, “Getting into Harvard or the Ivy League, even with good grades, was practically impossible because the competition was very high,” he says. Ophuls enrolled at Occidental because it was close to his parents—famed director Max Ophuls (La Ronde, Letter From an Unknown Woman) and stage actress Hilde Wall.

He majored in philosophy and took courses from the late professor Cyril Gloyn, an empiricist whose philosophical interpretations were shaped by William James and John Dewey. “It’s a looking at reality that began to suit me very well,” Ophuls says. “Dr. Gloyn has been a great influence on my films.”

At Oxy, Ophuls hung out with best friend (and Hollywood classmate) Don Loftsgordon ’50, who taught philosophy at the College from 1960 until his death in 1966. (The Donald R. Loftsgordon Award, created in 1966, is selected by the senior class and recognizes outstanding teaching at Oxy.) The pair was united in their introversion. “He had buck teeth, was tall and puritanical, and wasn’t very attractive to girls,” Ophuls says. “I was shy for other reasons. I didn’t have buck teeth, but I wasn’t a young Cary Grant either.” Apart from appearing in a campus production of Julius Caesar, Ophuls was known to skip classes—but not Gloyn’s—and play bridge at the Cooler.

When Ophuls’ parents returned to France in 1950, he became nostalgic and decided to complete his senior year at the Sorbonne. “That’s where I dropped out,” Ophuls says with a laugh. His Sorbonne professors were unremarkable. “Compared to Dr. Gloyn at Occidental, I found them very boring, dusty, musty, and academic,” he says. “That’s how I dropped out.”

Today Ophuls is retired and enjoys gardening, playing cards, reading (“I’m a great admirer of the No. 1 bestselling author in the world, John Grisham”), and watching movies at home. “I still like Hitchcock and Capra as much as I ever did,” he says. “I’m still not a great fan of Scorsese or the younger directors.”

As it happens, Ophuls got into documentary work for a very practical reason: He had bills to pay. After scoring good notices with his 1963 feature-length debut, Banana Peel with Jeanne Moreau, his follow-up, Fire at Will (starring ’60s spy-movie staple Eddie Constantine) was a flop that jeopardized his very livelihood. “It was a truly dreadful film,” he recalls. “Not only didn’t it click, but the producer lost money. And when producers lose money and you happen to be the son of a famous director who was considered difficult, well …” Ophuls trails off. At that point he was approached by French television, which wanted him to develop programs on contemporary history. The Sorrow and the Pity was initially banned from French television because it didn’t portray the country in heroic terms. But the film’s bravura transcended the controversy and it soon played to a rapt global audience.

Woody Allen, who name-checks The Sorrow and the Pity in memorable fashion in his own Oscar-winning film Annie Hall, explained to Occidental in an email that the 260-minute epic is “representative of high integrity and high seriousness.” “It’s a documentary masterpiece—very moving and complete,” Allen added.

Ophuls doesn’t dwell long on the kudos. “It happened to come out at the right time in French history and created a big scandal for political reasons,” he says of The Sorrow and the Pity. “I’ve done much better since.” He regards his best picture to be his last, The Troubles We’ve Seen (1994), about war correspondents in Sarajevo. The film met with mixed critical notices.

Now 77, Ophuls lives with one regret: He wishes he would have penned his memoir. It’s the story of escaping France and the occupying Nazis during World War II. Approached by a publishing house while making The Sorrow and the Pity, he declined the project because of time constraints. Ophuls says now that much of his fame has dissipated, it’s unlikely such a book will ever get written.

Curiously, France’s Cannes Film Festival has never seen fit to honor its adopted son (“Probably because I got an Oscar,” he laughs). Which is fine by him: Ophuls has a powerful canon of work that speaks for itself, asking viewers to come to terms with their own ethos. “I’d like them to walk away asking questions about whatever the topic is,” he says. “It can be about courage or journalism or about justice. I want people to think.”

[Editor’s note: In 2012, Ophuls completed Ain’t Misbehavin (Un Voyageur)—a documentary memoir, and his first film in 18 years—which screened at Cannes in 2013.]