U.S. Army Medical Corps veteran Richard Carlson ’60 on his Vietnam memoir, Mekong Medicine, and more

Mekong Medicine: A U.S. Doctor’s Year Treating Vietnam’s Forgotten Victims, by Richard W. Carlson ’60 (McFarland). In 1966, along with nearly half of his 1964 med school classmates, Richard Carlson was drafted into the U.S. Army Medical Corps. He applied to Vietnam’s Military Provincial Hospital Assistance Program—and as Carlson led a team in Bac Liêu province in the Mekong Delta from 1966 to 1967, he “religiously” chronicled his daily activities as well as life around him.

In the decades to follow, as he pursued a career in intensive care medicine, Carlson carried the yellowing typewritten pages of his Vietnam memoir from home to home. He reduced his clinical activities in 2017 and returned to the narrative at the urging of his wife, Barbara—and after her death in 2020, the task became a full-time endeavor. Mekong Medicine is a contemporaneous account of his team’s struggles with disease and war that affected nearly 600,000 Vietnam civilians.

In a Q&A for Occidental magazine with Erik Villard '90 (digital military historian and Vietnam War historian for the U.S. Army), Carlson discusses his Occidental education and the stories at the heart of his memoir.

How did your time at Occidental shape your personal and professional goals? Going to Oxy was familiar as my father’s medical office was a block away. History of Civilization made a lasting impression—a wonderful introduction to the scope of history and philosophy. I was premed and a biology major under the kindly guidance of John McMenamin ’40. Professor John Stevens became a mentor and friend and instilled in me a love of marine life, which later led to my studies of venoms. Oxy was a phenomenal grounding for academics and maturation.

What were the circumstances that led you to join the Army? I was an OB-GYN resident when I was drafted in 1966. I knew I’d soon be a general medical officer in Vietnam, so I volunteered for a new program in which medical teams worked in province hospitals. Upon being selected to command an Army unit in the Mekong Delta, my responses were both anticipation and anxiety.

What were the most challenging aspects of working in a civilian hospital in Vietnam? Province hospitals were built by the French in the early 1900s with few subsequent improvements. Ours had a rudimentary laboratory; no nursing care at night except the ER; animals, including rats, roaming the grounds, windows without screens or glass; primitive sanitation and electricity; and two patients typically sharing a bed with a rotting mattress.

The patients were simple farmers who lived as they had for more than a century. Superstition and folk remedies were prevalent. Malnutrition, parasites, and multiple endemic diseases were the norm, including tuberculosis, cholera, typhoid, malaria, plague, and dengue fever. A simple cut could be fatal as tetanus and other immunizations were rarely available. One-half of infants would not survive to adulthood. Chronic and congenital defects went untreated. Compounding these challenges, the war escalated with daily casualties, mostly women and children. They arrived in trickles or torrents—up to 50 a day. As in all wars, civilians suffered the most.

Our team had three doctors, only one of whom was a fully trained specialist to supplement two Vietnamese physicians, as well as 12 corpsmen and four USAID nurses. We received antibiotics and other medical supplies from USAID, although many items were stolen in Saigon. We worked in fear as the Viet Cong frequently shelled our location.

What were some of the most rewarding experiences? Despite the chaos and horror, we were able to provide life-saving care to many. The province medicine chief, a surgeon, was an inspiration. Some of my fondest memories are of the AMA volunteer physicians who each spent two months with us. They were a remarkable group and donated their skills to aid strangers in a remote, war-torn land.

How did your time in Vietnam influence your career and personal life after returning home? It was a life-changing experience. My medical teammate in Vietnam urged me to pursue a career of academics and research in public hospitals and medical schools while caring for the underserved. Following a Ph.D., I participated in the dawn of a new field—intensive care medicine. Teaching and mentoring physicians, nurses, and other healthcare providers are my proudest achievements.

Call Me Mule, directed by John McDonald ’71 and Nina Schwanse (3MulesMovie.com). John Sears, who calls himself Mule, has been roaming the western United States with his three mules for over 30 years. The 65-year-old and his animals sleep outside, claiming the right to move freely. Despite arrests and incarcerations, he keeps on fighting to maintain his nomadic lifestyle. His story may be unusual, but it has universal appeal, celebrating the creativity, courage, and resilience to choose an extraordinary way of life and defend his place in the world. Award-winning filmmaker John McDonald teams up with his daughter, Nina Schwanse, to make this compelling 94-minute observational documentary of Mule’s 500-mile journey to deliver a message to the governor of California. In March, Call Me Mule had its world premiere at the prestigious Thessaloniki International Documentary Festival in Greece, followed by its North American premiere at the Salem Film Fest in Massachusetts.

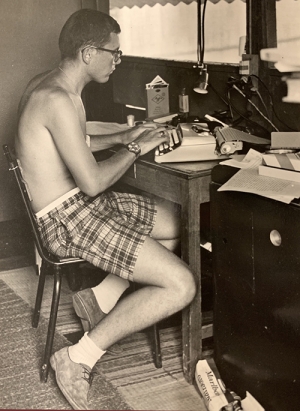

Top photo: Richard Carlson '60 in front of the hospital in Bac Liêu province in the Mekong Delta.