With two exhibits opening simultaneously and a new teaching space at Oxy, Assistant Professor Janna Ireland navigates her burgeoning career as she parents two growing boys

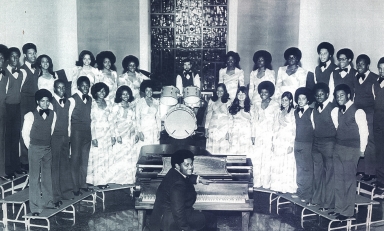

When South Carolina resident Julian Washington enlisted in the Army in 1966, he expected to be deployed to Vietnam for his service. Instead, he was sent to learn photography during basic training in New Jersey. After that, he did public relations and photojournalism while stationed in Germany, and he continued to pursue photography professionally after his discharge in 1969. “I grew up with my dad taking pictures and with cameras and lights being around,” says his daughter, Janna Ireland. “I took my first pictures at age 5 and then got into taking photographs in a serious way when I was 13 or 14.”

Even after graduating from New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts with a BFA in photography and enrolling in graduate school at UCLA four years later, Ireland still wasn’t thinking of photography as her ultimate career goal. “I thought of graduate school as something necessary to teach photography at the college level but still separate from working as a photographer,” says Ireland, who completed her MFA in 2013.

More than a decade later, Ireland’s career in photography is thriving, both academically and professionally. She’s midway through her third year as an assistant professor in the Art and Art History Department at Occidental. Her work is in the institutional collections of a number of major museums, and her editorial photography has appeared in The New York Times, The New Yorker, The Wall Street Journal, and The Atlantic, among other publications.

Most recently, back in January, two separate exhibits of her architecture photography opened on the same day. Running through September 27, Janna Ireland: Even by Proxy is a centennial exhibition of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Hollyhock House featuring 21 new images of the L.A. landmark taken by Ireland. Frontier Spirit: Paul R. Williams in California and Nevada—an overview of Ireland’s signature work documenting the pioneering African-American architect—recently concluded a six-week run at the Princeton School of Architecture in New Jersey.

While it’s coincidental that both exhibitions opened simultaneously, together they provide a window into Ireland’s growing portfolio, which examines such themes as family and domestic life, the built environment, and interactions between humans and the natural world. “We have been working on the Hollyhock House for a long time,” Ireland says from her office in Weingart Hall, which is adjacent to a newly renovated digital lab and darkroom for her students. “The opportunity to do the show at Princeton came together very quickly—I think they asked me to do it the week of Thanksgiving.”

When she was looking for a teaching job in Los Angeles, Ireland was attracted to Occidental’s liberal arts curriculum, its commitment to service, and the work that Oxy Arts was doing in the community. “I bring my classes to all the new shows at Oxy Arts,” she says. Last year she taught the senior seminar in studio art, working with a small group of students on their Senior Comps exhibition at Oxy Arts: “I was able to give each student a lot of individual attention, which they appreciated.”

This semester, Ireland is teaching three classes: L.A. Stories, which explores the relationship between place and photography; Photograph as Object, which utilizes Oxy’s spiffy new darkroom space; and Advanced Projects in Photography, a studio course in which students work in a genre and medium of their choosing. Enrollment for each course is capped at 15.

In the classroom, Ireland says, “It is really exciting to me to see students figure out how to tell their own stories as well as how to ethically and compassionately tell other people’s stories. Watching them learn and hearing the things that they think about is something that feeds into my own practice. It’s part of the work that I do as an artist.”

Nearly a decade ago, Ireland’s nascent career got a boost with a commission by the Julius Shulman Institute at Woodbury University in Burbank to document the architecture of Williams (1894-1980), who designed more than 2,000 buildings over the course of his 50-year career. “It started as a project that seemed like it would be short-term,” she says. “The idea is that I would have an exhibition of the work at the gallery that Woodbury University had at the time.”

The resulting exhibit, titled There Is Only One Paul R. Williams, opened to acclaim in 2017. (“Unlike conventional architectural photography that is intended to document every detail, Ireland’s shadowy photographs conjure a moody richness, inviting viewers to focus on unique architectural elements and how they may be experienced,” wrote Carmen Beals, an associate curator with the Nevada Museum of Art.) “That could have been the end of the project, but I was still interested in it,” Ireland says. “I still had my Google Alerts on so when a Paul Williams house came on the market, I found out about it, I still had all these opportunities to continue doing the work, So, I kept doing it.”

In March 2019, at the Barnsdall Gallery Theatre next door to Hollyhock House, Ireland spoke at an event moderated by former Los Angeles Times architecture critic Christopher Hawthorne for Occidental’s 3rdLA series. (The event was titled Is There an L.A. Sensibility? Place and Politics in Los Angeles Design.) That was her first visit to Hollyhock House, and her first exposure to Oxy.

“Because of that talk that I gave at Barnsdall Art Park, I was invited to speak at a conservation symposium at LACMA,” Ireland says, “and the publishers of Angel City Press were there.” That led to the opportunity to publish a book of Williams’ work [Regarding Paul R. Williams: A Photographer’s View, 2020], so Ireland continued to document his architecture. After its release, she says, “I stopped for a while because of the pandemic and I couldn’t go into people’s homes, so that could have been the end.”

But because of the book, Ireland got a magazine commission to go to Las Vegas and photograph some of Williams’ work, and pivoting off of that she was commissioned by the Nevada Museum of Art to photograph more of his work in Nevada. All totaled, Ireland devoted seven years to the study of Williams, which has resulted in a reevaluation of his legacy (a discourse that began in the 1990s, thanks to the work of his granddaughter and archivist, Karen E. Hudson).

In summer 2021, Ireland was contacted by Hollyhock House director and curator Abbey Chamberlain Brach about an exhibit to celebrate the centennial of the house, which was built in 1921. In her approach to the project, “It was important to me that the work have its own identity,” Ireland explains. “I decided pretty early on that I wanted the Hollyhock House pictures to be in color. Not only did I want them to be visually apart from the Williams photographs [which are all black-and-white], I wanted to really look at the way color is used in the house.”

Between the pandemic and the mechanics of working with the city of Los Angeles, which owns the property, it took more than three years to bring the project to fruition. Last summer, Ireland ended up making nearly 500 images of the property; she edited that down to 100 images, which she printed out and examined on a big table in her office.

After arriving at the final group of 20, “There was one image from the larger group that the curator wanted to bring in, so we made that addition,” Ireland says. (At the Hollyhock House show’s opening reception in January, she received the Shulman Institute’s Excellence in Photography Award, presented annually to a photographer “who challenges the way audiences look at physical space.”)

In a major 2024 exhibition titled Janna Ireland: True Story Index, the Santa Barbara Museum of Art and Museum of Contemporary Art Santa Barbara joined forces for a two-museum retrospective in what was labeled as “a mid-career survey and the largest presentation of Ireland’s photographs and installations to date.” Ireland is currently busy turning that exhibition into her next book, but there’s no timetable for its release yet: “We have a designer, but the curator who did the exhibition is pulled into other projects,” she says. “It’s very hard to get everyone together.”

For her next show, Ireland is one of more than 20 contemporary artists who work in self-portraiture exhibiting their work at the Forest Lawn Museum. Opening April 26 and running through August 10, Persona: Exploring Self-Portraiture will feature the work of these artists as well as historical self-portraits in a range of media, including paintings, sculptures, photographs, prints, fused glass, textile art, and illustrations.

While Ireland continues to explore self-portraiture in her photography (her go-to camera is a Fujifilm GFX100S), in recent years she has focused her lens more on her family. As a mother of two—sons Adrian and David are 9 and 7, respectively—“my relationship to family changed when I had children, of course,” she says. “Now, they’re in a lot of my work.”

Do her boys enjoy being photographed? “They either enjoy it or don’t mind it,” she says with a smile. “My youngest is very interested in art, but I’ve gotten very good at doing it quickly before they get bored.”