Six of Oxy’s longest tenured and most popular professors are retiring this spring—and some of their best and brightest students recount their impact and influence

Prof. Marcia Homiak

Prof. Eric Newhall

Prof. Robby Moore

Prof. John Swift

Prof. Keith Naylor

Prof. Sarah Chen

Marcia Homiak

Professor of philosophy

Years at Oxy: 45

Favorite course: “The Collegium, an interdisciplinary, team-taught course for first-year students—a class that no longer exists! The Collegium was a model of the wide-ranging first-year curriculum often offered by liberal arts colleges. It introduced me to many more students than I would normally teach in a single year and to all sorts of texts and questions that I would probably never have discovered (or had time to read) on my own. I am especially indebted to Jean Wyatt (for her lectures on George Eliot’s The Mill on the Floss), to Norman Cohen (for his lectures on William Morris’ News From Nowhere), and to Bob Janosik (for his lectures on historically important legal cases on abortion and affirmative action).”

Chris Varelas ’85: One lecture changed the entire trajectory of my life. I matriculated at Occidental in 1981 as a chemistry major hoping to go to medical school when I graduated. That was until a lecture by Marcia Homiak on Aristotle as part of the Collegium program.

In her uniquely charismatic and energetic lecture on the Nicomachean Ethics, she utilized the sixth game of the 1975 World Series [a 12-inning, Series-tying 7-6 win by Boston over Cincinnati] as the device to convey to us Aristotle’s definition of happiness. As a long-suffering Red Sox fan, I understood all too well that you had to focus on the journey and not the result. But now I understood why as opposed to wondering if it was just a rationalization for losing.

This made me start to wonder if the humanities could be a more rewarding and valuable education than that of chemistry. If philosophy could answer important questions such as What is happiness?, what other life challenges could be better addressed through the arts rather than the sciences?

I went on to take three classes from Marcia, choosing them based on the fact she was the professor rather than the topic. Her Feminism class took me to a world I could never have imagined, decades out in front of what the world was to become.

In true Aristotelian fashion, those classes allowed me to realize my highest and best skills and how they best aligned with the career and professional relationships I ultimately pursued. To the degree I have achieved any success, that success and the positive impact I have hopefully had on the lives of others can all be traced back to Professor Homiak. Thank you for what you gave me, and your tremendous contributions to the College. You will be missed.

Varelas is a founding partner of Riverwood Capital, a private-equity firm in Menlo Park, and an Occidental trustee.

Michael Gill ’87: Early in my freshman year some upperclassmen told me in exalted tones about an extraordinary lecture given by a philosophy professor named Marcia Homiak. The lecture used a blow-by-blow description of Game 6 of the 1975 World Series to teach a powerful lesson about Aristotle’s conception of the good life. It sounded rather unlikely. But later that year I heard the lecture myself. Every student in the hall was utterly gripped by Professor Homiak’s delivery. And every student walked out with a deep appreciation of both Carlton Fisk’s home run and Aristotelian eudaimonia. The upperclassmen were right. It was absolutely extraordinary.

I chose my courses at Oxy based almost exclusively on which professors I found most interesting. As a result, I ended up taking every class of Marcia’s that I could—and I was not the only one. There was a sizable group of us unabashed Homiak fans. We would trade with each the most recent insights we’d heard in her classes.

Marcia’s teaching was so compelling because of her fierce commitment to the significance of the material and to the importance of careful thought. In her classes, you felt that notions of knowledge, justice, and virtue really mattered. Thinking about those things could make your life better, could make you a better person. But only if you did it the right way—with close attention to detail, with the utmost logical care, with complete intellectual integrity. Marcia made philosophy the pinnacle of both academic rigor and personal importance. Her teaching embodied Socrates’ claim that the unexamined life was not worth living. You couldn’t ask for a more exciting or worthwhile college classroom experience.

I have since come to see that Marcia’s scholarship exemplifies the same values as her teaching: rigor combined with an intense focus on matters of real importance. Her uncompromising example has always remained one of my touchstones—a goal I aspire to whenever I consider philosophical issues and every time I step into a classroom. But her influence has not been only on future academics like me. The profound philosophical lessons they learned in her classroom have enriched her students in every walk of life.

Gill is professor of philosophy at the University of Arizona in Tucson.

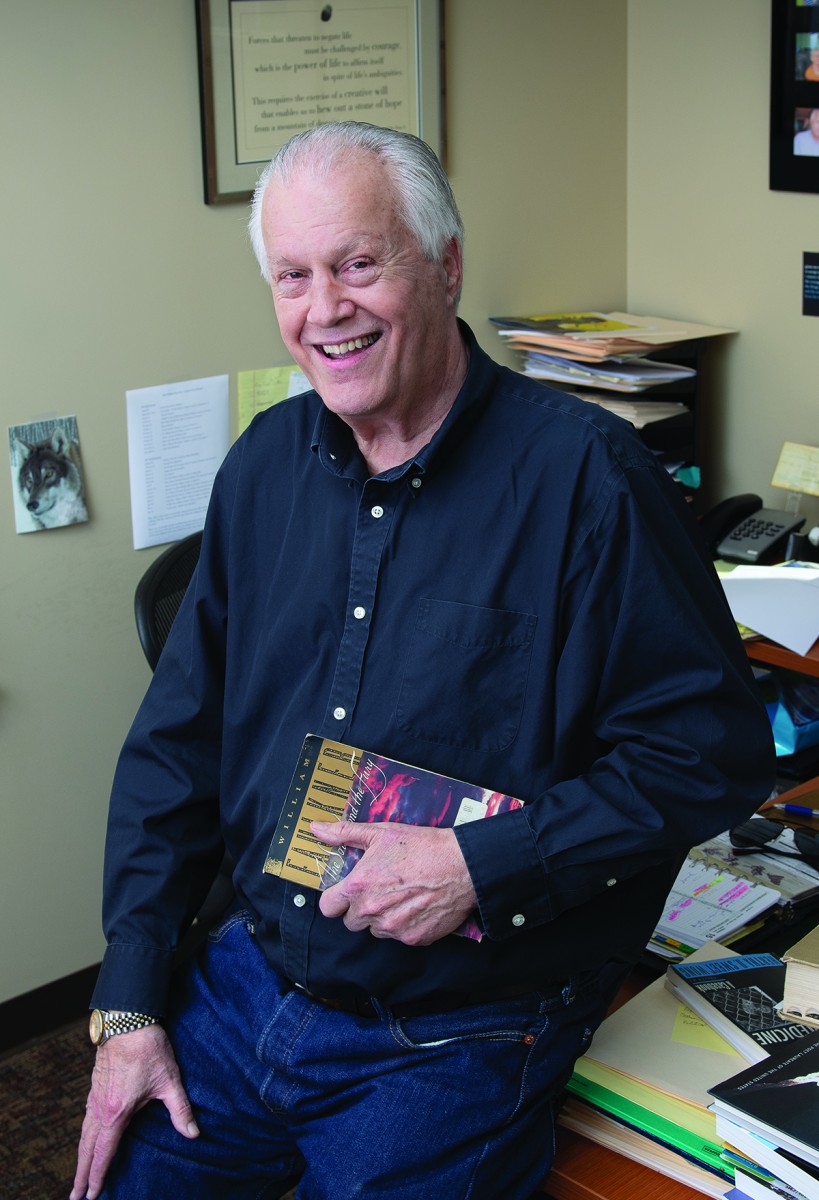

Eric Newhall ’67

Professor of English

Years at Oxy: 44

Favorite course: “English 372, Major Figures: Major Novels of William Faulkner and Toni Morrison. Both writers are Nobel Prize winners who write beautiful prose and deal (from quite different perspectives) with a range of subjects that citizens in a democratic society should engage: the relationship between past and present, race, gender, economic inequality, identity, nature and the erosion of the environment, the American Dream, community, and social justice.”

Plans after Oxy: “They are still a work in progress, but a few things seem clear. I’d like to become involved in some political action that gives direct support to American democracy outside academia. I look forward to reading for pleasure with no need to take notes for class the next week. [Wife] Jacki and I hope to travel more than we have in the past and to spend additional time with children and grandchildren. I’m sure that I’ll add additional items to my list, but this will do for a start.”

Daryl Ogden ’87: Reflecting on my Oxy years, I see Eric Newhall in my mind’s eye engaging with a student outside Swan Hall. He’s cradling books and class notes in one hand and gesturing with the other, emphasizing a key idea from that day’s lecture or seminar. Gesture completed, he inclines his head forward to listen to the student’s response, and the cycle repeats, seemingly on a continuous loop for the more than four decades of Newhall’s distinguished teaching and service to the College, his alma mater.

The image is a microcosm of Newhall’s career as one of the finest teachers who ever set foot on campus. It also provides a clue about his deepest values: realizing the credo of equity and excellence both within and beyond the classroom, which came to define his conviction about what an Oxy education should stand for.

In the classroom, Newhall elevated the importance of art and morality in American literature and culture without ever sounding moralistic. He unpacked rich meanings by framing questions that, in his hands, appeared to be endlessly generative. “What is Benjy Compson’s problem?” he asked, leaning forward, sleeves rolled up, his game face on. And away the seminar went, transporting 20 senior English majors from Eagle Rock to Faulkner’s Mississippi. He accomplished similar results with Heller’s Yossarian, Pynchon’s Oedipa, and Morrison’s Sethe—and countless others from the landscape of American fiction.

Newhall’s institutional imprint on Oxy is indelible. He conceived and led the Multicultural Summer Institute for 15 years, over two separate tenures, preparing generations of incoming underrepresented students for success and modeling what diversity at a great liberal arts college should look and feel like. As director of the Core Program, Newhall spearheaded the creation of Living and Learning Communities, which placed all students in each of the 32 Core Writing Seminars into common residence halls, designing living arrangements that cultivated social relationships and built writing skills that shortly translated into one of the highest four-year graduation rates in Oxy’s history. In these examples of his contributions toward extending and redefining the classroom, Newhall scaled teaching and learning excellence at Oxy.

Because his manner is understated, Newhall’s competitiveness can sometimes be missed. I witnessed this competitiveness up close as his teammate on our off- campus intramural basketball team, where Newhall impressed with a smooth lefty jumper and soft-spoken trash talking.

Newhall’s trash talking—which is at least somewhat tongue-in-cheek and always funny— traveled easily from the basketball court to academia as he tweaked me, for example, in asserting the primacy of a certain Southern writer (“Gatsby’s OK, Ogden, but give me Faulknerian toughness over romantic egotism”).

For Newhall’s students of my era, “Faulknerian toughness” meant surviving eight thick Yoknapataphwa County novels in 10 short weeks, an immersive literary experience that made us feel as though we were spending the term “abroad” in Jefferson, a fictionalized version of Oxford, Miss. That Newhall could inspire a group of undergraduates to take up the challenge of that ambitious syllabus underscored his competitiveness as a professor who always sought to surpass himself and make magic happen in the classroom.

And, following Faulkner’s Dilsey, after 44 remarkable years at Oxy, Eric Newhall endures.

Ogden was an English major who took four courses from Newhall, including an independent study in American women writers. Newhall also served as the second reader on Ogden’s honors thesis and as his academic adviser. Ogden later pursued graduate studies in English at the University of Cambridge and the University of Washington, where he earned his Ph.D.

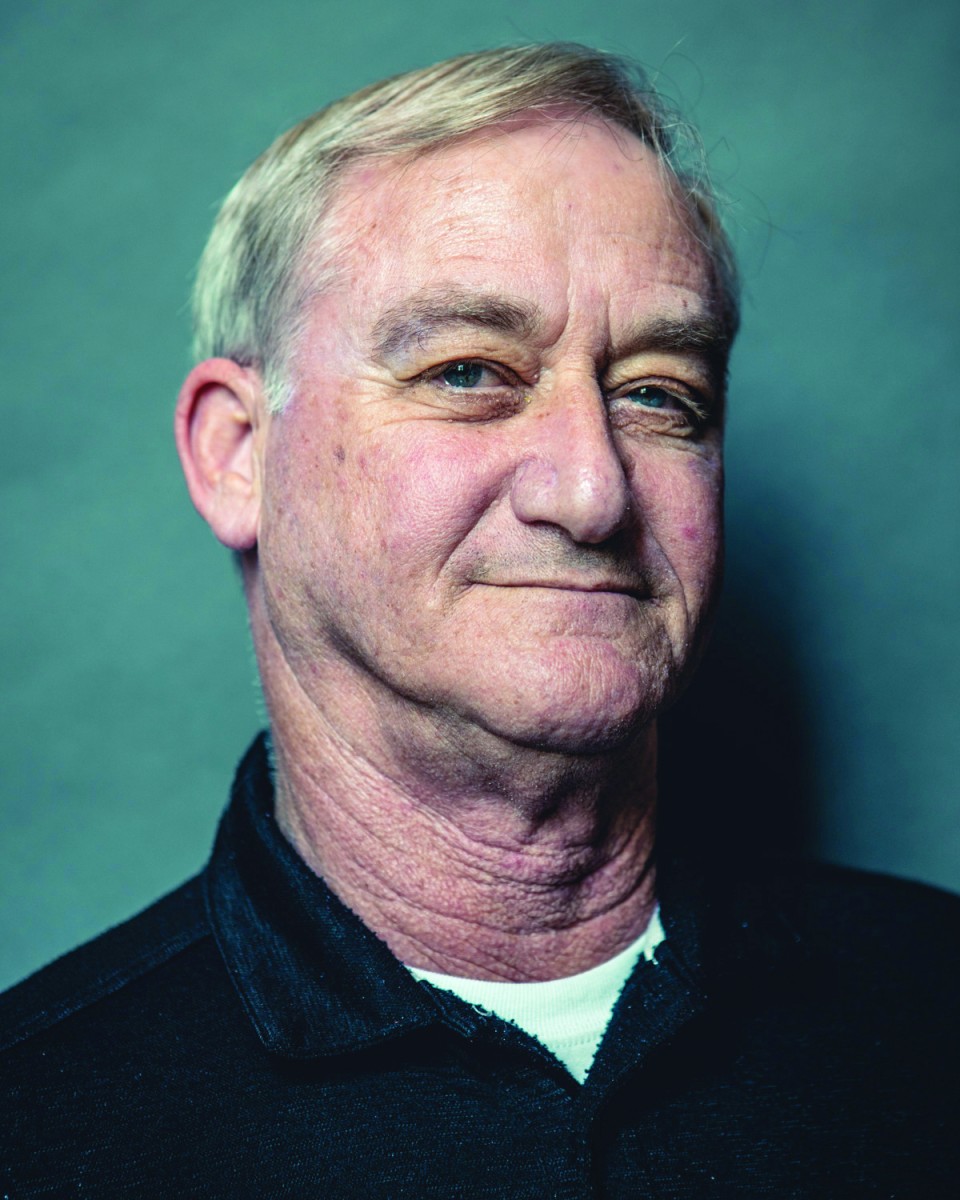

Robby Moore

Elbridge Amos Stuart Professor of Economics

Years at Oxy: 41

Favorite course: “Economics 101, Principles of Economics I. For many students, it is the only course in economics that they will ever take, and I have taught it almost every year I’ve been at Oxy. I like it because I find it the most challenging course to teach—it introduces students to an entirely different way of thinking about many issues. As a result, many students find it quite difficult to grasp some of the basic principles, and I try to use a wide variety of pedagogy to enable them to learn and apply these basic principles.”

Plans after Oxy: “My wife and I plan to spend a couple of months in the late summer and fall each year on Cape Cod, where she has lots of family. We also hope to travel more. I may at some point decide to teach my course in Personnel Economics (Econ 326) at Pomona College, something I have done previously.”

Walter Impert ’96: In 1978, Harvard’s loss was Oxy’s gain when a young assistant professor of economics named Robby Moore traded Harvard crimson for Occidental orange. That same year, at age 4, I moved with my family from Belgium to the United States. Our paths crossed 14 years later, when I was a freshman in Robby’s Introductory Microeconomics class. I had written a high school paper on economics and thought that I would like the subject in college. My guess was correct, but it may have been Robby’s teaching more than the subject matter that got me hooked. He taught us to use economics to analyze everything from gift giving (which results in inefficiency or “dead weight loss”) to laziness (the indifference curve for income versus leisure), well before “Freakonomics” entered the popular culture. I soon declared economics as my major and proceeded to take Robby’s classes on Intermediate Microeconomic Theory and Labor Economics, and I worked as a teaching assistant in his introductory classes. Ultimately, Robby taught me and a generation of other Oxy students a new way to think about the world.

Impert is a partner with the law firm of Dorsey & Whitney, where he leads Seattle’s trusts and estates practice group.

Laura Kawano ’02: I entered Oxy with a vague idea that I would major in economics, but it wasn’t until Robby Moore’s Intermediate Microeconomics course that my interest was solidified. In his classroom, I was drawn to the tools of economic thinking, learning new methods to analyze decision-making processes.

As it turns out, Professor Moore had a large impact on my own decision-making process. When I started to consider a career as an economist, he quickly became the person I turned to for advice. Although not my official adviser, Professor Moore met with me often to discuss how to best prepare for graduate school. During my senior year, he also gave me the unique opportunity to serve as his teaching assistant, a position that he had negotiated when he became president of the Faculty Council. I graded problem sets (which I was too naive to realize was a terrible task) and ran review sessions. This initial venture into undergraduate teaching reinforced my resolve to join the academic community.

Prior to my graduation, he gave me a copy of Edward Lazear’s Personnel Economics with a note wishing me success in my future career. Robby incorrectly guessed my ultimate field of interest, but I did discover my chosen field in another of his courses, Economics of the Public Sector. Having gained an interest in public policy, I focused on public finance in graduate school, later joined the public sector as an economist for the Treasury Department, and am now a research affiliate at the University of Michigan’s Office of Tax Policy Research. When I was a visiting professor at the Wharton Business School, I dug up my notes from Robby’s course when creating my own undergraduate course on taxation. He may be happy to learn that those Wharton students did paper tax returns for the “Nurd Family”—one of Robby’s many teaching legacies.

After Oxy, Professor Moore became Robby—as he insisted—and a friend. He has been a source of encouragement during those major milestones of my career. Undoubtedly, his supporting letters of recommendation were major factors on this journey. Robby’s work has contributed to the field of personnel economics, but his legacy is also in his investment in and dedication to the personnel around him—his students, colleagues, and friends. I am grateful to count myself among them.

Kawano is a research affiliate with the Office of Tax Policy Research at the University of Michigan’s Stephen M. Ross School of Business.

Jim Blackett ’15: Robby Moore was one of the first and last professors I had at Oxy: In my freshman year I took Econ 101 with him, and in my senior year I took his Personnel Economics seminar. On both ends of my time at Oxy, I appreciated his clear teaching, intuitive understanding of the subject, willingness to help outside of class time, and support for students’ wide variety of interests. Professor Moore helped me with my Fulbright application to Mexico, which made possible one of the most impactful years of my life. During my senior year he also offered me a job as a group tutor for his Econ 101 students. I appreciated this opportunity to approach the subject from the perspective of a teacher, and I was reminded that teaching is one of the best ways of learning.

As a teaching credential student, I often think about the challenge of introducing students to a new field of study. Professor Moore was one to learn from in this regard: He conveyed the significance of the economic way of thinking and its role in each of our lives. His wisdom in economics combined with his care for students made him an invaluable member of the department, one who will be remembered by generations of Oxy alumni.

Blackett is a graduate student in music education at Cal State Long Beach.

Sue Schroeder ’84: As self-confident young women in a major dominated exclusively by men, my classmates and I felt that we had to work extra hard to compete with our peers and that the professors were tough on us. Looking back, I realize that this toughness was exactly what we needed to learn to be successful at a high level in the business world. Through his no-nonsense style, Robby Moore was a role model for showing us that it is not enough to be smart—you have to go above and beyond and put in the hard work to demonstrate your knowledge of and passion for the material. He had high expectations that you bring your “A” game to every class. Robby motivated us to try to live up to those high standards.

Years later, I reconnected with Robby when I was on the Occidental Board of Trustees and he was involved in the Faculty Council. Through our conversation over cocktails, we realized that my profession as an executive compensation consultant touches on several of the topics that he covers in his senior seminar on Personnel Economics. I was honored when he invited me to serve as a guest lecturer in one of his classes, which I have now been doing almost every year for the last 10 years. It is a thrill for me to be back in his classroom and be reminded of the high standard of excellence that he expects.

Robby gave me a gift of a laser pointer to use for my PowerPoint slides in his class—one that I have used for many of my business presentations over the years. It always makes me think of Robby and that I need to bring my “A” game. It will be a bittersweet experience to guest lecture in one of his last classes this spring. Robby exemplifies the outstanding characteristics of an Occidental education—commitment to excellence, dedication to teaching, and genuine caring and concern for the future of his students. What a great accomplishment to have made such a positive impact on so many lives!

Schroeder is a partner at Compensation Advisory Partners, an executive compensation consulting firm with offices in New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, and Houston.

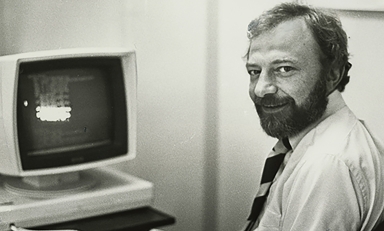

John Swift

Professor of English

Years at Oxy: 38

Favorite course: “It’s really difficult to say. I was hired mainly to teach the modern novel in English, I think, and the various courses that I designed to do that became good friends: It was great to re-encounter them over the years and follow their changes. But my most exciting teaching experiences were maybe with modern poetry, when students would (occasionally) suddenly understand why this difficult stuff was important and beautiful after all. Or with the junior seminars on modernism and psychoanalysis that I taught off and on in the 1990s and 2000s, where students had a first significant brush with writing and presenting real literary research.”

Plans after Oxy: “I’m moving to a small town on Maine’s central coast, where I plan to do some gardening and fishing, and to help my wife, Cheryl, with her own hobby, raising Labrador retrievers. And I have several research and writing projects to occupy me. I doubt that I’ll be bored.”

Malia Boyd ’91:Swan Hall. Freshman Writing Seminar, fall 1987. Led by an English prof named, of all things, John Swift, we used Virgil’s Georgics as a springboard to discuss whether the natural world was benign or malign. As we sat there, warily eyeing the fresh cracks in the walls caused by the massive Whittier Narrows earthquake, which had occurred days earlier, the answer seemed obvious. Yet there we were, ignoring endless ironies and possible collapse, just getting on with the business of life and learning. It was vintage Swift.

I took a course from him every year I was at Oxy. When I declared my major and he became my adviser, he officially took on a role I had already assigned him that first day in Swan Hall. We could literally ask him anything about life or literature; in class or out, he remained accessible, affable, with an unshakeable willingness to take us seriously. He really listened, never condescending, never pshawing an idea—and I came up with some doozies, especially in his Freudian Interpretations of Literature course.

He had an indefatigable allegiance to plaid button-downs, and these ivory cowboy boots. He wore them every day. The left boot squeaked when he walked. He also loved The Eagles. In 1987 Los Angeles, this aesthetic was decidedly … not hip. That, too, was a life lesson: Be yourself. Do the thing you love to do. Life will be good.

My senior year, while Swift, Fineman, and Newhall stood nearby, I remember dancing on a table in Braun Hall after my senior comps with some other English majors, wondering how I’d get through the next phase of my intellectual development without him. Turns out, I didn’t have to. To this day, he faithfully responds to every email I send. His tolerance knows no bounds.

Virginia Woolf’s novel Jacob’s Room, which I read in his Woolf/Cather course my sophomore year, begins with the lines, “So of course … there was nothing for it but to leave.” I imagine Swift having this thought the day he decided to retire, dreamily staring at the campus from the top of Fiji. In reality, I think he just wants to walk the wilds of the Maine coast, shovel snow, run the dogs, and spend time with his family. I guess I’m OK with that, though it makes me sad to think of him not at Oxy and so very far away. All I can say is that he’d better have a good Internet connection, because those emails are gonna keep coming.

Boyd is director of marketing at Manoa Senior Care in Honolulu.

Leah Ordonia ’04: Professor Swift was my Core Program professor in a first-semester writing seminar about Los Angeles past and present. Having been raised in Los Angeles very close to Oxy, I remember being captivated by how his analysis and presentation of the great thinkers who have assessed L.A. as a focus for study helped me re-experience my relationship with the city I thought I knew so well with new eyes and a new perspective. With Professor Swift’s expertise, I could see how I fit within various socio-historical-literary discourse within the world’s “melting pot.” As a young woman of color, that experience was and still is very meaningful to me.

I continued to learn under Professor Swift in his Modernist Literature class, where he introduced me to the work of Willa Cather. At the time I was double-majoring in English and comparative literary studies and visual arts with a pre-law emphasis, and I was drawn to Cather’s work thematically as well as to her life story, which exemplified a romanticized idealism of the Western frontier and a pragmatism that tackled political trends and legal issues of her time. Under Professor Swift’s mentorship I was awarded a Ford Fellowship to conduct independent research that investigated philosophical legal trends that influenced Cather’s writing and feminist themes in her work. With his help, I shared my work at various research conferences at the regional, state, and national levels, and eventually developed my work into my senior honors thesis.

Through the years I have kept in touch with Professor Swift because he has been a continued source of wisdom and mentorship, not just academically but in life in general. When I made the very difficult decision to pursue a career in 3D animation instead of law school to give myself a chance to pioneer in an exciting new field, and then later in recent years when I decided to expand my creative career into writing fiction for children, Professor Swift has continuously helped me see my intellectual adventurousness and creative vigor as gifts and still continues to mentor me through life. I am ever grateful for his endless support, his guiding wisdom, and especially his friendship.

Ordonia is a visual development and concept design artist living in Boston. She works for PBS affiliate WGBH.

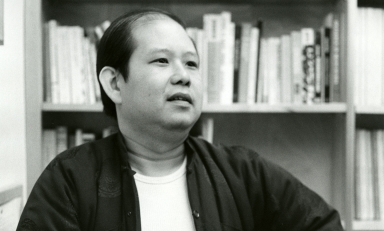

Keith Naylor

Professor of religious studies

Years at Oxy: 31

Favorite course: “I will avoid the Solomonic choice of my favorite religious studies course, and speak instead of my Nature Writing and the Environment course in the Cultural Studies Program. I taught the course seven or eight times. That course was full of classic and contemporary nature writing texts that inspired us and challenged us to change the way we live. To consider the natural world around us as our source, even in the face of human exploitation and abuse of nature, was almost a relief. Our field trip to Eaton Canyon Natural Area (after reading of John Muir’s trip there in 1877) heightened our environmental consciousness, and opened us up to the great diversity of Southern California ecosystems.”

Plans after Oxy: “No comment.”

Justin Marc Smith ’00: “Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about things that matter.” The previous words are an often cited but likely paraphrased quote attributed to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Professor D. Keith Naylor has dedicated his career to speaking “about things that matter.” I write in honor of him because he taught me, as he has countless other students, to speak about things that matter.

What does one say about a person at the end of a brilliant academic career? That they were excellent in the classroom, yes. That they were accomplished in the academy, yes. That they stood shoulder to shoulder with colleagues, faculty, and students to create change, yes. Keith has done all of this and done so with a deep compassion and veracity that draws our attention and admiration as we reflect on the course of his career.

When I think of Keith, I think of meeting him for the first time as a new student at Oxy. I think of the gentleness and clarity as he explained the parameters of the major and I think of the excitement and feeling of safety knowing that he would be my adviser. Of his passion that came forth in the classroom as he nearly vibrated day after day in our African-American Religious Traditions course. Of lunches and dinners and conversations about life, academia and politics. When I think of Keith, I think of integrity.

Keith will forever be associated with Occidental College. For his students, it is impossible to recount our time at Oxy and not think of Keith. And we are blessed to have learned from him—not just in his classes but in experiencing what a good life looks like lived out. I remain indebted to Keith for his guidance, care, and the friendship he has cultivated with me in the years since graduation. We are colleagues now. Professors in similar fields. But Keith will always remain my mentor, my professor. I look forward for what is next in life for Keith. I lament with that generation that will not know his teaching. I remain thankful for who Keith is to me and Oxy.

Smith is assistant professor of biblical and religious studies at Azusa Pacific University.

Julius H. Bailey ’93: I took Dr. Keith Naylor’s Religion in America course and my life would never be the same. Walking into his classroom, I had never encountered someone so passionate about the study of religion. Dr. Naylor encouraged me, a quiet and reserved first-year student, to share my thoughts in class discussions on a range of challenging and complicated topics involving religion. Every class was different. One day he might play music; another day there might be a debate, or we might closely examine and analyze a primary document.

One class with Dr. Naylor led to another until I eventually fell in love with the academic study of religion. The next thing I knew I was in graduate school, and today I regularly teach classes like Religion in America myself. When I’m preparing for a class session, I still think about how Dr. Naylor might approach the topic and how he would bring the subject alive for the students sitting in my class. I think about how patient he would be and how much time and energy he would expend coaxing out the very best of every single student in the classroom. I can’t think of another person who had such a profound and lasting impact on both my personal and professional growth. I’m extremely grateful to have had Dr. Naylor as a teacher, adviser, colleague, and friend—and as anyone who has ever taken a course with him can attest, you will never look at the world the same way again.

Bailey is professor of religious studies at the University of Redlands.

Sarah Chen

Professor of East Asian studies

Years at Oxy: 30

Favorite course: “Actually, I have two: Elementary Chinese (Chin 101)—watching students’ excitement and progress in learning is most rewarding; and Translating Chinese (Chin 460)—I enjoy having native speakers of Chinese and native speakers of English read, translate, and discuss modern and contemporary works of Chinese literature in their original Chinese texts.”

Plans after Oxy:“Travel; read more Chinese, Japanese, and world literature; go to concerts; practice piano; learn Spanish; relearn French.”

Nancy Yao Maasbach ’94: As a gritty, New York City American-born Chinese, I experienced severe culture shock when I arrived at Occidental. Characteristics of sunny Southern California were foreign to me, especially assimilated, well-adjusted, third-gen Asian Americans from the West Coast and Hawai‘i, and deep and varied discussions about political correctness, identity, and faith. In many ways, Professor Sarah Chen served as my personal connector: a link to my ancestral past, my immigrant upbringing, and my yet-to-be-known future.

Professor Chen is a professor for all. I admired her subtle but intentional fairness: There was no guanxi in her class, no preferential treatment. I knew that she could see and sense each student’s growth as we meandered our path toward adulthood through scholarship. Her teaching was infused with generous smiles and light laughter, but her lyrical presentation of Chinese language kicked my butt. Her class pushed me to clean up my academic sloppiness. “There are about 10,000 Chinese characters; you need to know about 3,000 characters to interact in Chinese. How many do you know?” Not enough. It was that simple prompt that created a bizarre discipline in me. I knew she was disappointed when we did not perform; I knew she was pleased when we did well.

Beyond the Chinese language classes, it was Professor Chen’s class on Modern Chinese Literature that changed me. I eagerly read and reread stories by writers like Lu Xun, Ding Ling, and Shen Congwen. Professor Chen infused us with these writers’ hopes and dreams, energizing us to pursue our own unique paths.

Maasbach is president of the Museum of Chinese in America in New York City.

Brian Bumpas ’12: A reticent sophomore walks into his first Chinese 101 class, motivated not by a passion for the language but by a liberal arts requirement. He doesn’t know it yet but he just changed the fundamental trajectory of his life. Ten years later, I still use Chinese on a daily basis. That was Oxy’s promise: Come with a modicum of curiosity or receptiveness, and our professors will give you lifelong passions. Sarah Chen made that promise reality.

Professor Chen (or, as we know her, Chen Laoshi) instilled in her students a long-lasting enthusiasm for Chinese language and culture. Her love of Chinese cinema carried over into the classroom, as we debated the consequences of Mao’s Cultural Revolution through the medium of director Zhang Yimou’s tragic classic To Live. And her generosity was tangible, exemplified in the abundance of mooncakes she brought in for the Mid-Autumn Festival or the class-wide Chinese dinner that she organized every semester, all at her personal expense.

But most important, she challenged us. Two to three hours of daily homework assignments and 1½ hours of Chinese class every other day seemed grueling at the time, especially on top of every other commitment that makes an Oxy degree so rewarding. But the process enhanced our work ethic and time management skills, and strengthened my personal character.

Fast-forward 10 years: Three of us became Fulbright grantees in East Asia (me, Annie Ewbank ’13, and Elizabeth Kennedy ’12), one started a successful international business bridging the United States and China (Sunil Damle ’13), and one is at the National Committee on U.S.-China Relations (Nick Young ’12). I wouldn’t be surprised if Chen Laoshi left as indelible an impact on their lives as she has on mine.

Chen Laoshi is a deeply kind, giving person. She cares immensely about her students and the program that she directed. Without her, I would never have developed this passion for Chinese. She encouraged me at several critical stages in my life, and gave me valuable advice that continues to serve me well to this day. I’ll never forget her insistence on learning the notoriously difficult traditional Chinese characters, and the countless hand cramps that ensued. But sure enough, that lesson proved prescient, and built a strong foundation that many students educated at other institutions lack.

I am honored to call Chen Laoshi a mentor and a friend, and I know she will leave a lasting positive legacy on Occidental’s Chinese program. I can’t wait to see what comes next—for her and for the program.

Bumpas is a subject matter expert at Thresher, a computer software company in Washington, D.C.