Utilizing biomass burial and carbon credits, Mast Reforestation CEO Grant Canary ’05 is on a mission to revive scorched landscapes in the American West

Across the country, and particularly in the West, charred landscapes tell the stories of wildfires that are burning hotter, faster, and more often due to climate change. From 1992 to 2023, the United States saw an increase in annual wildfire acreage from 2.5 million to 7.5 million acres.

“That increase is the equivalent of New Jersey burning every year,” says Grant Canary ’05, CEO of Mast Reforestation, a Seattle-based startup whose mission is to make reforestation scalable, using technology to revive forests too far damaged to naturally regenerate.

“People assume planting trees is cheap because of the dollar-per-tree model which has been the same price for decades,” Canary says. “But reforesting just a few thousand acres can cost millions.” After a high-severity fire, there is little value left in the timber to harvest to pay for reforestation. Historically, the federal government has subsidized the additional cost, but that gap has grown.

Beyond wrecking homes and scenery, the conflagrations are eradicating the results of what are known as mast years, a natural phenomenon that occurs every two to five years during which trees produce an atypically large crop of seeds, fruits, or nuts to ensure a species’ continued survival. These “seed banks” also are a critical food source for wildlife. Severe fires, some reaching temperatures of 2,200 degrees, burn topsoil and seeds, leaving barren land that can’t be revived without help.

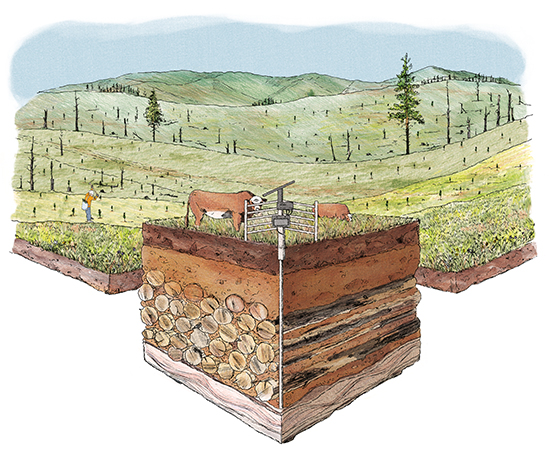

In just the last four years, Mast has planted millions of seedlings in the fire-scarred American West. Currently Mast is collaborating with a Montana family landowner near Billings to restore forestland devastated by the 2021 Poverty Flats fire, which destroyed more than 60 percent of their trees. Mast will bury the landowner’s stockpiled dead trees (originally slated for burning), generating an estimated 30,000 tons of carbon removal credits, which can be sold to fund reforestation efforts following wildfires.

Canary says his “integrated model” for replanting forests—seed sourcing, planting, monitoring, and carbon financing—provides a blueprint for rapid ecosystem recovery. Mast collects seed varieties from 11 Western states, replanting regions with trees that are compatible with new climate realities.

With around 25 employees at Mast’s headquarters and 200 workers at peak operation time at its nurseries, Canary is deeply involved in every facet of the work, from creating funding strategies to visiting burned landscapes. “That’s one of my favorite parts,” he says. “Being out in the forest reminds me why we do this.”

Growing up in Oregon, Canary’s love of natural spaces began early. “My heroes were Davy Crockett and Robin Hood,” he recalls. “I had two tree forts as a kid.” His father helped start Salem Mountain Rescue, and he saved timber companies millions of dollars as a tax attorney.

Canary attended Occidental on a Margaret Bundy Scott Scholarship, which covered about half the cost of his tuition. He majored in sociology with a minor in urban and environmental policy, served as captain of the men’s water polo team, and was both vice president and president of the student-run Programming Board, which brought Jane Goodall to campus in 2004. The liberal arts experience was foundational, he says: “A lot of the education I got was really instructive on how the world worked.”

After graduation, Canary had a brief stint with the U.S. Green Building Council, a nonprofit organization dedicated to transforming the built environment (the man-made structures, features, and facilities in which people live and work). After living abroad for 10 years, he was selected for a management development program for Vestas Wind Energy, where he worked on projects in China and Denmark.

While working toward a master’s in engineering at Universidad de la Sabana in Bogotá, Colombia, he founded BioSystems Co., which used food waste to feed insect larvae to create sustainable fish feed. After BioSystems was acquired by Canadian-based Enterra Feed Corp. in 2012, Canary was responsible for supporting Enterra CEO Brad Marchant in fundraising and investor relations, project management, business development, and expansion strategy.

But Canary sought to make an impact directly on atmospheric emissions due to the threats posed by climate change. After returning to the United States, he explored multiple business models, prompting a friend to joke, “You’re going to end up a hippie planting trees.” Those words rang prophetic.

Leaning into the possibilities afforded by drone technology, Canary founded DroneSeed in Beaverton, Ore., in 2016. (The company was rebranded as Mast Reforestation in 2021.) It was accepted to Techstars—a leading pre-seed venture capital firm—and at the time, Canary estimated that its drones could plant 800 seeds per hour by firing seeds into the ground using compressed air, a task that would take a human a full workday. “We see drones as forestry’s tractor,” he told MarketWatch reporter Sally French.

In 2021, Mast acquired Silvaseed, a 154-year-old company that manages the majority of seed for 11 western states, Mast’s priority remains restoring forests with native species appropriate for each microclimate, which Canary says safeguards biodiversity and ensures long-term forest health.

He and his team rely heavily on consulting foresters, local experts with deep understandings of local ecosystems. Mast and the foresters write site-specific replanting plans—called “prescriptions” in the industry—using geographic information system data, seed zone knowledge, and ecological modeling. “They’re like family doctors,” Canary says. “They know what native species will compete and what will thrive in post-fire conditions.”

Consider the Henry Creek watershed in the foothills of Oregon's Cascade Mountains. In 2020, the Beachie Creek fire swept through the area and burned tens of thousands of acres of mature Douglas fir forest. The following spring, Mast worked to collect native tree seed from nearby unburned areas. Mast has planted more than 150,000 seedlings on the 1,000-plus acres it manages, which serves as a watershed for the nearby capital city of Salem, as well as habitat for local wildlife.

Over the last nine years, the U.S. forestry industry has grown by more than 40 percent, to an estimated $288 billion in 2025. In February, Mast announced a $25 million Series B funding round to scale its expansion into biomass burial, a “durable and scalable carbon removal solution” that Mast is integrating with its restorative reforestation services. That’s on top of a $36 million Series A round in 2021 around the time of the Silvaseed acquisition. (Mast is also the parent company to Cal Forest Nurseries, which was established in 1978 and grows most of California’s conifer seedlings.)

Forests aren’t just beautiful settings, Canary notes: They’re also critical infrastructure, providing clean water, air filtration, carbon storage, pollination, and wildlife habitat that are an essential life support system for the planet. They’re also important “carbon sinks,” absorbing more carbon dioxide than they release. Through photosynthesis, trees convert carbon dioxide—given off by forest fires, as well as during the burning of coal, oil, and natural gas—into wood, leaves, and roots, where they store the material.

In some parts of the country, nurturing forests is politically and economically propitious. In 2010, the city of Medford, Ore., was given a choice by the Environmental Protection Agency to build a $100 million water-chilling plant or plant trees to cool and purify its waterways. “They chose trees,” Canary says, “because forests do what no machine can do—naturally, efficiently, and for free.”

Mast has found its place in the voluntary carbon market, a global marketplace in which companies and organizations subsidize other companies’ and organizations’ efforts to cut carbon emissions, thereby reducing their emissions liability. Mast sells carbon credits, which fund reforestation. “This is as big a shift as the cotton gin, or the telephone, or the creation of double-entry accounting,” Canary says. “It moves humanity from valuing solely the extraction of natural resources to a model that values and provides the capital to invest in the services ecosystems provide, such as pollination and cleaning water and air.”

Voluntary markets have become a popular way to cut harmful greenhouse gas emissions. Clients pay Mast to remove dead trees and bury them in engineered vaults, thus removing the carbon in the logs from the atmospheric cycle and storing it underground, where it will be inert for 100 to 1,000 years. Mast’s clientele includes small family forests, timber companies, tribal nations, public lands, nonprofits, and tech companies like Shopify.

In 2023, Fast Company named Mast to its list of the World’s Most Innovative Companies in the “Social Good” category. The following year, Mast was named to CNBC’s prestigious Disruptor 50 list. “For people of my generation, climate change feels urgent,” says Micah Kirscher ’20, a public relations associate with New York-based Redwood Climate Communications, which helps climate nonprofits and tech startups (including Mast) with climate storytelling. “A lot of us got into this work because there’s a clear, pressing threat,” adds the Washington state native, who majored in diplomacy and world affairs at Oxy. “You graduate from college and you’re excited about work opportunities, and then it hits you that the climate situation is dire.”

Canary knows the challenges at hand. Prior to 1990, low-severity fires in small acreage were expected to regenerate 90 percent of the time; former Cal Fire Chief Ken Pimlott, speaking to 60 Minutes, described a 10,000-acre fire as a “career fire” so large that a firefighter would only see it once in their career. These days, that’s not the case. “I describe the soil as like a crème brûlée,” Canary says. “The good seed in a low-severity fire is in the yellow part of the crème brûlée, and it’s all happy. In a high-severity fire, you blowtorch the whole crème brûlée and the seeds are destroyed as well.”

Faught wrote “The Morning Showman” in the Summer 2024 magazine.

Top photo: Grant Canary '05, photographed in Seattle's Carkeek Park on July 19, 2025.