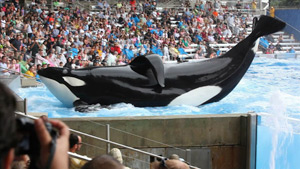

Acclaimed and unsettling, Blackfish is a high-water mark for documentary filmmaker Gabriela Cowperthwaite '93. What does its success bode for her career—and what will the fallout be for SeaWorld?

Some of the best investigative journalism starts with a single question. For documentary filmmaker Gabriela Cowperthwaite '93, that question was: Why would a killer whale at SeaWorld Orlando brutally attack and kill its trainer? After all, for 50 years SeaWorld has been telling the public that killer whales are docile creatures who are happy living in captivity and performing tricks for delighted audiences. "I'd always thought if I had to be an animal in captivity, I'd probably choose to be a Shamu, getting hugs and fish," Cowperthwaite says. "I was really ignorant about that world."

A Denver native, Cowperthwaite had been making documentaries for television for 12 years (including Animal Planet, Discovery, ESPN, History, and National Geographic) when she read "The Killer in the Pool"—Outside magazine writer Tim Zimmermann's July 2010 story about Dawn Brancheau, a top trainer at SeaWorld who had been killed by a 6-ton bull orca named Tilikum on Feb. 24, 2010. The fact that Tilikum was connected with two earlier tragedies (a trainer's drowning in 1991 and the accidental death of a tourist in 1999) only muddied the waters further.'I couldn't understand why an intelligent, sentient animal would bite the hand that feeds it," Cowperthwaite says. "This was a strange story, and I couldn't shake it. When I began developing the documentary, I was shocked by what I learned."

Drawing on interviews with former trainers, expert witnesses in a lawsuit against SeaWorld, a former whale hunter, and a host of found footage that's a testament to her perseverance, Blackfish screened to critical acclaim and standing-room-only audiences at the 2013 Sundance Film Festival last January. After a three-day bidding war in Park City, Utah, the film was snapped up for distribution by Magnolia Pictures and CNN Films. Despite its unpleasant subject matter, Blackfish grossed nearly $2.1 million in theaters following its July 19 release. It received an even bigger boost when CNN broadcast the documentary in late October, amassing 20.6 million viewers over the course of 17 airings in the weeks to follow.

With each successive wave of exposure, the long tail trailing Cowperthwaite's film has only grown. Blackfish has made the short list of 15 documentaries up for Academy Award consideration (nominations will be announced January 16) and is one of five finalists for best documentary feature by the Critics Choice Awards. The CNN exposure has prompted at least eight musical acts, from Barenaked Ladies and Heart to Willie Nelson and Martina McBride, to pull out of a scheduled concert series at SeaWorld Orlando. "Gabriela's films are catalysts for change," says Tim Case of Supply & Demand Integrated, who signed Cowperthwaite for commercial ad representation on the strength of her 2009 documentary feature, City LAX: An Urban Lacrosse Story. "They start movements."

Before this movement started, Cowperthwaite was just another parent making the pilgrimage to SeaWorld, having taken her 7-year-old twin boys, Max and Diego, to its San Diego location twice. "I think we all had the cringe factor, which is the way a lot of us feel when we go there," she says. "You're bombarded with products the moment you walk through the gate. And then you see trainers standing on the noses of killer whales, and it feels so undignified—for the animal and for the trainer. I would think to myself that something's wrong, but you're kind of anesthetized—there's thumping music and bright colors, and everyone around you is smiling. So you think, 'How can something that's so bad make people so happy?'"

That was before Brancheau's grisly death planted another question in Cowperthwaite's mind: Why would Tilikum kill his trainer?

Interviews with animal behavior experts and former SeaWorld trainers embellished the reporting done by Zimmermann (who has an associate producer credit on Blackfish). Some of the most disturbing footage in Blackfish is of calves being separated from their mothers during capture. (In November 1983, then-2-year-old Tilikum was captured as a calf off the east coast of Iceland.) Cowperthwaite was also able—through the Freedom of Information Act—to include chilling in-house footage of actual killer whale attacks on trainers, as well as of the whales' apparent misery in captivity. (The footage surfaced in connection with a lawsuit filed against SeaWorld in 2010 following Brancheau's death by the U.S. Department of Labor's Occupational Safety and Health Administration. "Perseverance is everything in documentary," Cowperthwaite has said.)"I can't say this was an easy film to make," says Cowperthwaite. "For two years we were bombarded with terrifying facts, autopsy reports, sobbing interviewees, and unhappy animals—a place diametrically opposite to its carefully refined image. But as I moved forward, I knew that we had a chance to fix some things that had come unraveled along the way. And that all I had to do was tell the truth."

Cowperthwaite majored in political science at Oxy, citing Professor Jane Jaquette's Women, Politics, and Power class as influential on her eventual career path. She was pursuing a graduate degree in political science at USC when, during a trip to Guatemala, she saw a woman toting a video camera in her backpack and interviewing children on the street. "That's a cooler version of myself right there," she thought later. And even though she had never picked up a movie camera, the die had been cast.

"Most of us documentarians don't think anyone's ever gonna see our films on purpose." Cowperthwaite says. "It's impossible to explain what it means to get into Sundance." (The film has since made the festival circuit globally, from Melbourne and Moscow to Rio de Janeiro and Seoul.) "You make these films because you're compelled to tell a truthful story, almost in spite of yourself. So when I saw a line wrapped around the building for our Sundance premiere, I hunched down in the car seat and started crying."

SeaWorld's initial reaction to the film was to send a detailed critique to about 50 movie critics before it even hit theaters—a move that The New York Times called "an unusual preemptive strike." The email read in part: "In the event you are planning to review this film, we thought you should be apprised of the following. Although Blackfish is by most accounts a powerful, emotionally-moving piece of advocacy, it is also shamefully dishonest, deliberately misleading, and scientifically inaccurate."

The move backfired. "From a marketing perspective, SeaWorld did completely f*** up," says Tor Myhren '94, worldwide chief creative officer of Grey New York and a close friend of Cowperthwaite's, having collaborated with her on City LAX (which follows his brother Erik's efforts to establish an inner-city lacrosse program in Denver). When Blackfish was about to open in five theaters in mid-July, nearly six months removed from the initial hoopla, "it really did not have a lot of momentum," he says. "It had done well at Sundance, and then it kind of went quiet."

After the SeaWorld email went viral, Blackfish was suddenly "the most talked-about documentary of the year," Myhren says. "It was a classic, classic PR mistake by SeaWorld—and I'm very glad they made it."

As the story gained traction, Blackfish fanned out across the county, hitting its widest release (99 theaters) in its sixth week. By then, it had sold more than $1.7 million in tickets. And SeaWorld—which draws about 10 million visitors a year to its parks in San Diego, Orlando, and San Antonio, Texas—went silent in the tsunami of bad press.

According to Cowperthwaite, as much as 70 percent of SeaWorld's revenue comes from its killer whales—no drop in the bucket for a company that generates close to $1.5 billion in revenue annually. And while SeaWorld (which filed a public stock offering last April) claims that the negative PR generated by the film has not affected ticket sales, "the actual numbers prove them to be lying," Myhren claims. Cowperthwaite says SeaWorld's ticket sales declined 13 percent after the theatrical release, but in an aggressive marketing move, SeaWorld began giving away tickets to bolster its numbers.

SeaWorld's Blackfish-induced headaches began well before the canceled concerts. After seeing the film on CNN, musician Joan Jett wrote to SeaWorld asking them to stop using her song "I Love Rock 'n' Roll" as opening music "for its cruel and abusive Shamu Rocks show." Even before that, the Pixar creative team behind the forthcoming sequel Finding Dory nixed a storyline involving a killer whale that included a water park.

On November 8, more than 50 demonstrators with People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) lined up outside the Pasadena Tournament of Roses headquarters, a number of them wearing orca costumes, and holding signs such as "Boycott SeaWorld" and "Get Orca Abuse Out of the Rose Parade." (The design for the SeaWorld-sponsored float, called "Sea of Surprises," prominently features the park's signature whales.) The protests continued into the holiday season, with 2009 grand marshal Cloris Leachman adding her voice to PETA's cause.

"They pretend this apex predator is a huggable pet," Cowperthwaite says. "That has 'parade' written all over it." By catering to families and kids with loud music and over-the-top productions, SeaWorld's whole philosophy, she believes, is "to anesthetize us so we buy it hook, line, and sinker; turn off our critical thinking; and just smile without giving the issue any real thought."

"SeaWorld is not an institution that is dedicated to education or rehabilitation or release," she continues. "Their main directive is profit through entertainment. That's it. You can sit through entire Shamu shows and never even hear the words 'killer whale.'"

Cowperthwaite would like to see the end of orcas in captivity, starting with the demise of their breeding programs. Currently housed orcas would not survive in the open ocean, but they could be relocated to enclosed sea pens, she suggests—even Tilikum. "He's a tough one, right? His teeth are all broken from biting on steel gates. He's hopped up on antibiotics. He's old. He floats lifelessly on the surface of the water. So in some ways he's the worst candidate for any kind of release."

The Icelandic government would like Tilikum retired to a sea pen in Icelandic waters, she says, "so he can live out his life with a bit of dignity. It's tough, because you're not sure if he would survive for very long. But my theory is, could his life be any worse?"

After spending more than two years making Blackfish and another year talking about it, Cowperthwaite says she is "percolating" about her next project, but those close to her predict great things. "She will put herself in any situation, which makes her an amazing documentary filmmaker," says Myhren. "I've never seen a director who's able to get more honest emotions and more authentic feeling from her subjects than Gab. It's so awesome to see her taking that talent and putting it into films that matter in the world."

And watch out, world, because, according to Case: "She is just warming up."

Photo by Max S. Gerber.