The Tony-winning set designer and legendary Yale professor, who died last fall, dedicated himself to theater and to teaching, Ann Sheffield ’83 recalls

Soon after she moved back to California, theater designer Ann Sheffield ’83 went to a play at the Mark Taper Forum at the invitation of a friend. “I didn’t know the play and I didn’t look it up,” she says—it was Enigma Variations, by playwright Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt—but when she walked into the theater, she practically gasped as she looked at the stage. “I wish I had done that,” she recalls. “The play hadn’t started—I hadn’t even gotten to my seat—and I was salivating about the space.” When she finally sat down, she opened the program and just laughed. “I’m like, ‘Oh my God, it’s Ming’s. Of course.’”

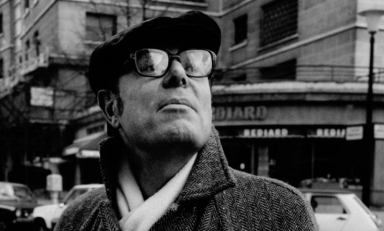

Sheffield was more than familiar with the work of Ming Cho Lee ’53, the Tony Award-winning set designer (for K2 in 1983), 2002 National Medal of Arts Recipient, and 2013 Lifetime Achievement Tony honoree, who died Oct. 23, 2020, at his home in Manhattan. A studio art and theater double major at Oxy, she studied with Lee at the Yale School of Drama and is now a professor and scenic designer at UC Santa Barbara.Sheffield got involved in theater design at the encouragement of Tom Bloom, “who was single-handedly holding down design in the department at the time,” she says. Soon after, then-Professor of Theater Arts Omar Paxson ’48 got Sheffield involved in Oxy’s Summer Theater program, and she felt “lucky” to have landed in a community of artists.

Unbeknownst to Sheffield, Bloom entered her work into the Kennedy Center American College Theater Festival. Her scenic design for Paxson’s play Laughing in the Sea Wind won the district competition in Flagstaff, Ariz., and took top honors at the national level in Washington, D.C., where Lee was the adjudicator. Meeting Lee, she admits, “I did not realize the significance of his place in the history of American theater design.” He encouraged Sheffield to apply to his “little program in the East”—which she did, after a year of working in small L.A. theaters and doing props for some low-budget films.

In addition to studying with Lee at Yale for three years, she worked as his assistant for two of those summers between school. “Ming was not very commercial theater oriented, but he was such a busy freelance artist,” she says, working in regional theater and the Metropolitan Opera. “He allowed me to be his assistant in his studio in New York, which is also his family apartment.”

Ming’s wife, Betsy, became like a surrogate mom to Sheffield, especially when it came to lunchtime. The work day rarely started before 10, she says—“They had their breakfast and their whole thing—but you weren’t going to leave that building until after 7. Betsy made the most incredible lunch spreads, a combination of Jewish and Chinese food like you would not believe. I lived on that food those two summers because I couldn’t afford anything else.”

Prior to branching out into teaching, first at the University of Oklahoma and later at Cal State Fullerton, Sheffield enjoyed a long association with Tony Walton, an Oscar-, Emmy-, and Tony Award-winning production designer. “I probably learned more about moving scenery and scene changes from Tony,” she says. “But Ming taught me more in terms of the aesthetics of a place and a sense of balance within asymmetry—the empty space versus the detailed space.”

Last fall, with Lee’s health rapidly declining and his 90th birthday approaching, son Richard Lee ’81 reached out to Sheffield, asking her to record a short video greeting. “So I went off somewhere in nature and I just said, ‘I love you, Ming. I miss you, Ming. And I thank you for everything.’ Within a few weeks, he was gone.

“I wish I could assess a student’s work as instinctively as he was able to do,” she says. “When I’m designing, it’s often an emotional response to the work and sometimes I don’t know where it comes from. That’s a really hard thing to teach, to tell a student, ‘It will come,’ you know? I’m humbled by being able to have been in Ming’s orbit for a little bit.”