From February 5-9, 2020, Professor Shana Goffredi was chief scientist for a research cruise aboard the R/V Western Flyer to explore the fascinating undersea world off the Southern California coast, from San Diego to Santa Monica.

The Southern California Borderland is an active tectonic area with diverse physical and chemical characteristics. Despite being heavily trafficked by marine vessels, this region remains largely unexplored below the surface. We plan to visit 5 specific sites (between 800-1020 m depth), each chosen as a unique natural laboratory in which to investigate the cycling of carbon, sulfur, nitrogen, and other nutrients in the deep sea. Our primary research objective is to investigate the identities, rates and activities of specific groups of deep-sea microorganisms, both free-living and in symbiosis with marine invertebrates, and link those to prevailing geological and chemical conditions.

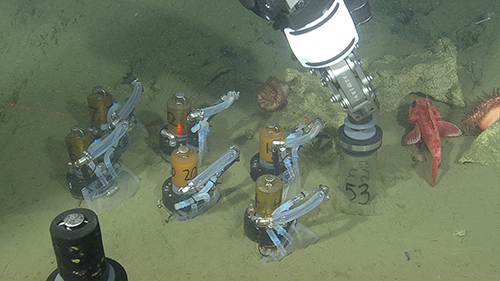

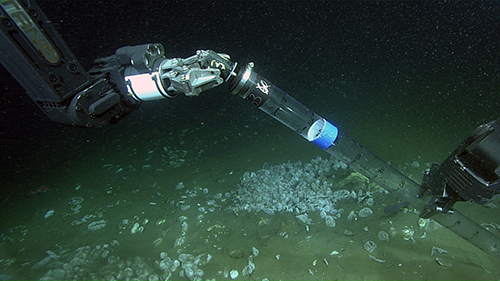

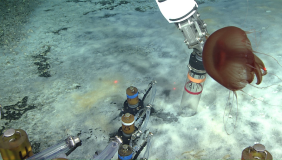

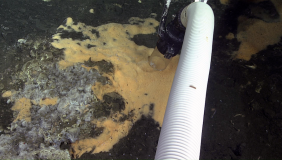

The researchers onboard (a team of animal biologists, microbiologists, ecologists, geochemists, submersible pilots, and the ship’s captain and crew) will collaborate to study the variability among communities fueled by chemosynthesis–those that use chemical energy rather than energy from the sun. This type of metabolism is common in the deep-sea and can be harnessed only by microbial life and the inventive animals that team up with them. These areas are often called ‘seeps’ in that sulfide and methane emerge (or seep) from the underlying sediments to fuel dense biological communities.

Tune in for our daily blogs as we visit the following sites:

- The Del Mar Seep - This site was discovered in 2012 only 30 miles offshore by graduate students from Scripps Institution of Oceanography on a cruise aboard the R/V Melville. This seep hosts a variety of fascinating marine life, including colorful bacterial mats, clam and tubeworm aggregations, and large carbonate outcrops.

- The Santa Monica Basin – This area is the site of 3 of our specific seafloor targets, large mounds with active venting of methane gas, and an ancient fossil seep that was extensively mapped in 2010 by scientists at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute.

- Rosebud – In 2011, scientists at Scripps Institution of Oceanography sank a 20-m long fin whale that had washed ashore after it died from a ship strike. Since then, the ecosystem at Rosebud has been thriving, and includes numerous worms and snails that are found nowhere else on Earth. Learn more about the unique animal life at whalefalls.

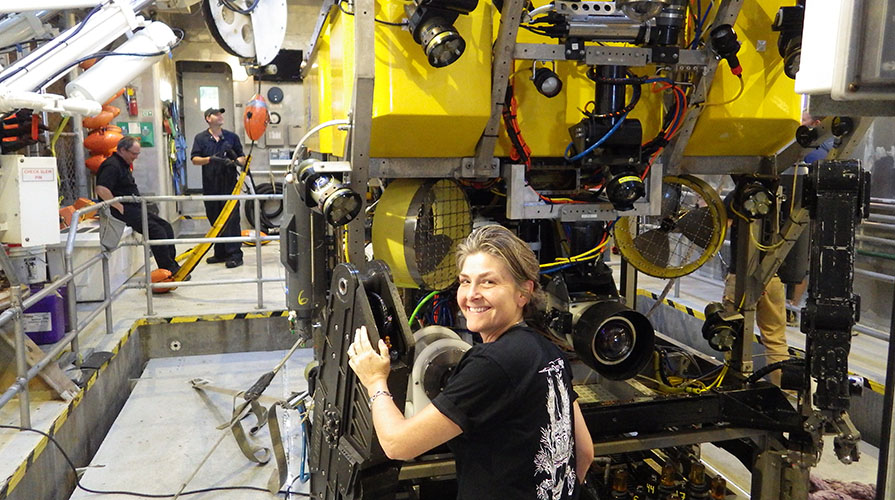

Ship and Submersible

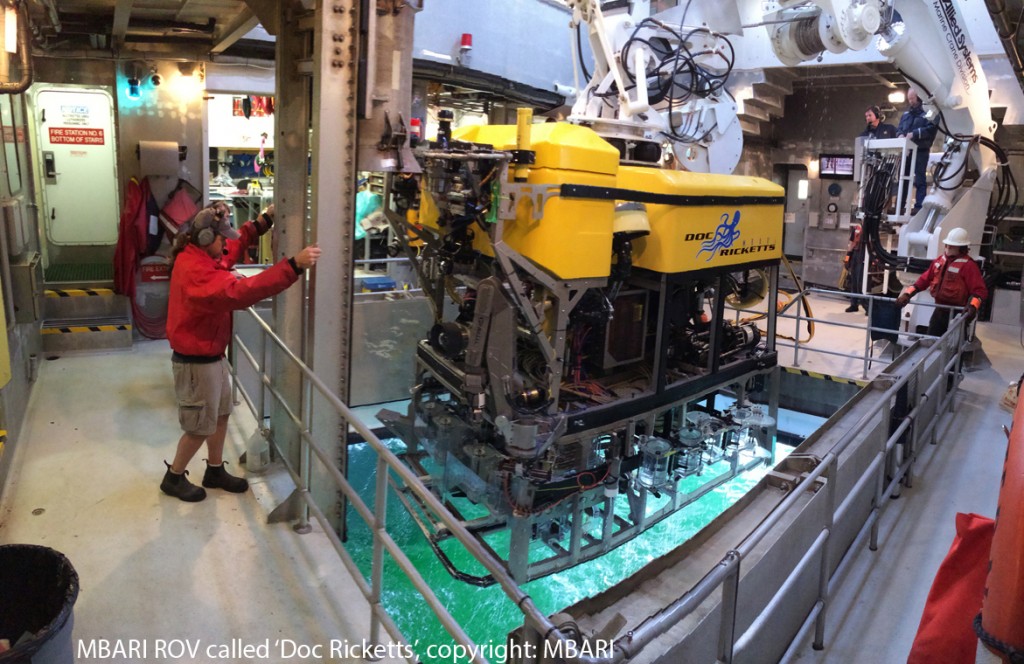

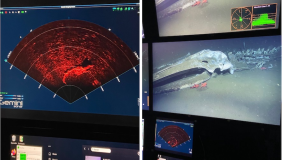

We’ll be aboard the RV Western Flyer, owned and operated by the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute. The Western Flyer is a 117-foot oceanographic research vessel designed specifically for deploying, operating, and recovering tethered submersibles. In order to visualize and sample the seafloor, we’ll be using the 10,000 lb remotely-operated submersible ROV Doc Ricketts, built in 2009.